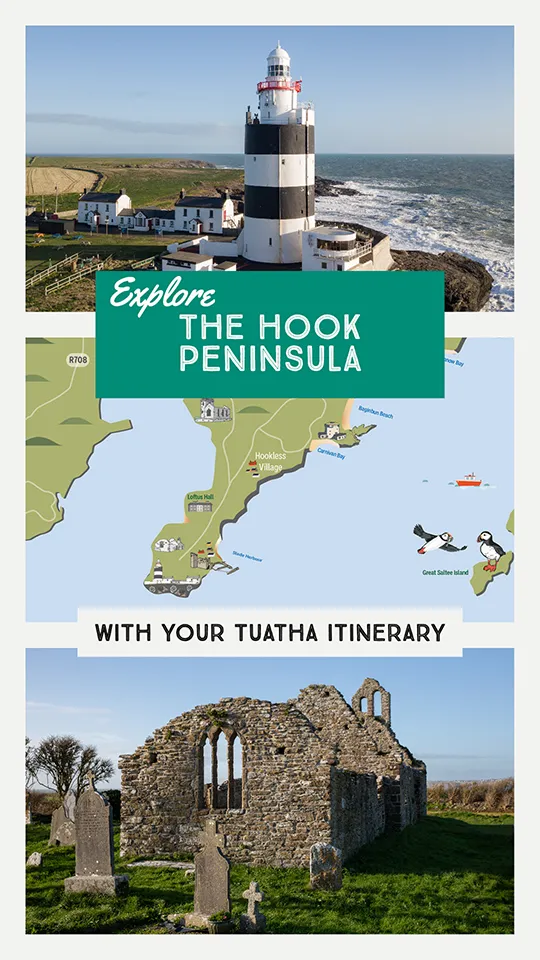

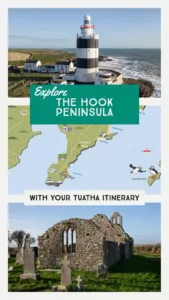

The Saltee Islands

The Saltee Islands, located 5 kilometres off Kilmore Quay in Wexford, are a wonderful place to get close to nature. The 120-acre Great Saltee Island, is home to thousands of seabirds including Puffins, Manx Shearwaters and Gannets. Great Saltee Island is privately owned by the Neale family, who inherited it after their father, the self-declared Prince Michael the First died in 1998. The family are kind enough to welcome visitors on day-trips, to experience the breathtakingly beautiful scenery and the wealth of natural heritage.

Our visit in July 2020 came after months of lockdown, and it was the very best place to shake off such a long spell of being stuck indoors. On the trip out on the ferry it felt like the first time I could fully breathe again, and the sense of freedom was helped by a beautiful sunny day with calm seas. Near the island, we transferred to a small dinghy to be brought ashore below a flight of stone steps. The island is stunningly beautiful, and made colourful by bluebells in the early summer, though they were long gone when we arrived in July. Instead we were treated to bright purple loosestrife, or clusters of delicate sea spurrey and sea campion but it is predominately covered either by a thin sward of grass grazed near to the bone by rabbits, or dense bracken that has swallowed much of the island.

One of the tales that is commonly told about the Saltee Islands is that they are anywhere between 650 million and 2 billion years old. However, it appears that the islands are largely made up of the pink-coloured Saltees Granite that formed as molten rock around 480 million years old, pushing into the more ancient gneiss of the Rosslare Formation that is located close to Kilmore Quay.

A glacial ridge of stone and gravel known as ‘St. Patrick’s Bridge’ forms a natural causeway that connected Little Saltee with Kilmore Quay at low tide, and has posed a threat to shipping over the centuries.

For practical information about visiting this site Click Here

The Saltee Islands, located 5 kilometres off Kilmore Quay in Wexford, are a wonderful place to get close to nature. The 120-acre Great Saltee Island, is home to thousands of seabirds including Puffins, Manx Shearwaters and Gannets. Great Saltee Island is privately owned by the Neale family, who inherited it after their father, the self-declared Prince Michael the First died in 1998. The family are kind enough to welcome visitors on day-trips, to experience the breathtakingly beautiful scenery and the wealth of natural heritage.

Our visit in July 2020 came after months of lockdown, and it was the very best place to shake off such a long spell of being stuck indoors. On the trip out on the ferry it felt like the first time I could fully breathe again, and the sense of freedom was helped by a beautiful sunny day with calm seas. Near the island, we transferred to a small dinghy to be brought ashore below a flight of stone steps. The island is stunningly beautiful, and made colourful by bluebells in the early summer, though they were long gone when we arrived in July. Instead we were treated to bright purple loosestrife, or clusters of delicate sea spurrey and sea campion but it is predominately covered either by a thin sward of grass grazed near to the bone by rabbits, or dense bracken that has swallowed much of the island.

One of the tales that is commonly told about the Saltee Islands is that they are anywhere between 650 million and 2 billion years old. However, it appears that the islands are largely made up of the pink-coloured Saltees Granite that formed as molten rock around 480 million years old, pushing into the more ancient gneiss of the Rosslare Formation that is located close to Kilmore Quay.

A glacial ridge of stone and gravel known as ‘St. Patrick’s Bridge’ forms a natural causeway that connected Little Saltee with Kilmore Quay at low tide, and has posed a threat to shipping over the centuries.

For practical information about visiting this site Click Here

Puffins billing on the Great Saltee Island • Wexford

The Archaeology, History and Folklore of The Saltee Islands

The landscape of the Great Saltee Island • Wexford

There is surprisingly little written about the archaeology and history of the Saltee Islands, and the Archaeological Survey of Ireland has relatively few monuments recorded. Neolithic artefacts have been discovered in the past, suggesting that the islands were occupied (or at least seasonally visited) during prehistory. Possible promontory forts (a site type that can date as early as the Late Bronze Age / Iron Age, up to the early medieval period) have been tentatively identified on both the islands, though the thick covering of bracken masks much of the contours of the islands. An ogham stone was found on Great Saltee Island in 1925, and this may be evidence of an early church site. This stone is now on display at Ferns Castle.

The name Saltee is believed to derive from the Old Norse salt øy, meaning ‘Salt Island’. The Old-Irish name of the Great Saltee is ‘Eninis’, but it is long obsolete in Irish. Eninis suffered a Viking raid in AD 922 in which 1,200 Irish were slain. If Eninis was indeed the Great Saltee Island, this would raise the possibility of a large community (presumably monastic) being located there. Alternatively it may have acted as a way-station or trading base for the Vikings of Ireland, and it may have been that which was raided by a rival band of Vikings.

In 1177 the islands were under the control of Hervey de Montmorency, the uncle of Richard de Clare (known as Strongbow) who led the Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland. He granted the islands to Canterbury, and they in turn, later granted the islands to Tintern Abbey in 1245. It is likely that the lay community of Tintern farmed the islands, and when Tintern was suppressed during the Dissolution of the Monasteries, it was noted that the abbey still owned a large portion of the islands. They were later leased by a number of noble families (including the Colcloughs). In the 17th and 18th centuries, the Saltee Islands were a notorious haunt of pirates.

The landscape of the Great Saltee Island • Wexford

Early in the 19th century, the Parle family bought the islands and started cultivating wheat, barley and potatoes, with the majority of the island used for pasture. One of the family, John, had a great reputation as a strong man; he could lift up two sheep, one under each arm, and put them into a cot (small boat) to take them to the mainland. By 1860, about 20 people were living on the Great Saltee. The bird colonies on the islands had become famous during the 19th century, and it was a popular place for shooting parties. In 1943 Great Saltee Island was bought by Michael Neale, who declared himself Prince Michael of the Saltees.

The wonderful National Folklore Collection has a number of tales about the Saltee Islands. One of the more common folktales describes how the islands were formed, when St. Patrick chased a devil from Tipperary all the way to Wexford. During the chase, the devil took a big bite out of a mountain and he spat two mouthfuls in the ocean off Kilmore Quay forming the Saltee Islands.

Another story describes how General Bagenal Harvey and John Colclough fled to the Saltee Islands after the defeat of the 1798 rebels at the Battle of Vinegar Hill. They hid in a cave for some time, before being discovered when soldiers noticed smoke coming from a crevice in the rocks. The men were captured and brought to Wexford, where they were executed.

A rather odd tale describes a time when cattle used to be left to graze on the islands. One day the men went in a boat to the island and they saw a little woman in a shell. The little woman used to milk the cows and make butter. The men told the little woman they would tell and she said “You may when you will think of it.” They never thought of it until the day she died.

Upper left: the ancient stone of the Saltee Islands • Lower left: the remains of a structure • Right: the Saltee Island Ferry

Top: the ancient stone of the Saltee Islands • Middle: the Saltee Island Ferry • Bottom: the remains of a structure

The Seabirds of The Saltee Islands

Puffins • Great Saltee Island

The island is an important sanctuary for seabirds, with puffins, gannets, guillemots, razorbills, cormorants, great black-backed gulls, kittiwakes and manx shearwaters all calling the Saltee Islands their home. The gannets are perhaps the most easily found, and among the most impressive. We saw two gannet colonies at pretty close quarters, a smaller one on a rock stack off the southern shore at the eastern end of the island, and a much larger one at the western end. The smell coming from that colony in particular was pretty elemental. Reminiscent of pig-farm with undertones of fish. Thankfully when we got close to the colony the strong breeze was blowing it away downwind so it was possible to sit and watch the swirling multitudes of these stunning birds. On land they are a little clumsy and ungainly, but in the air they are something else entirely. They hang and soar effortlessly, and suddenly plunge like a divebomber into the sea. The gannets were only outdone in noise by the kittiwakes – their onomatopoeic call kittiwake kittiwake kittiwake is a near constant background soundscape, especially around the easternmost part of the island. The great black-backed gulls also made a real impression on me. They are large, and their powerful presence on the island marked them out as an apex predator. However, as wonderful as the other birds are I can’t hide the fact that one of the main motivations for me to visit the Saltees is that they are home to a population of puffins.

The section below has a brief introduction to some of the main birds that you might encounter on the Saltee Islands, though of course the time of year is crucial. The best time to visit the Saltee Islands is between April and the end of July, after that many of the birds (including the puffins) will leave the island to head back out to sea. If you would like to read more about the lives of these wonderful creatures, I highly recommend The Seabird’s Cry by Adam Nicolson, a wonderful book that will help you see our ocean voyagers in a whole new light.

Puffins • Great Saltee Island

The Saltee Islands Puffins | Puifín

Puffins with a bill full of sand eels • Great Saltee Island

Puffins feed on sand eels and other small oily fish in the waters around the island. These wonderful birds can live to be more than 30 years old and they typically mate for life, returning to the same burrow year after year. Puffins are one of the most monogamous creatures on Earth! A study of the puffin colony on Skomer Island, Wales, discovered a ‘divorce’ rate of less than 8%. They usually stay with the same partner for life, and return to the same burrow to find each other every year.

They only raise one chick per year, so it is vitally important that they experience as little disturbance as possible: please keep a good distance from them if they are at their burrow. After they leave again in August the mating pairs go their separate ways, their bright beaks and feet dull and fade as they head out to spend winter alone on the storm-tossed seas.

Puffins are wonderfully charismatic, but as a species they are in drastic decline. They are now on the dreaded Red List of species vulnerable to extinction. A census of the Great Saltee Island puffin population taken in around 1999–2002 recorded 1,822 pairs. That number plummeted down to just 50 pairs by 2018. One of the key reasons for that catastrophic collapse of population is the presence of brown rats on the Saltee Islands, who eat the eggs and young pufflings. As each pair lays only one egg each year, the puffins are very vulnerable to such predation. In response, Ireland’s National Parks and Wildlife Service are attempting to carry out a programme to eradicate the rats on the islands, to save the Saltee puffin population.

Saltee Island Gannets | Gainead

Gannet • Great Saltee Island

Despite being a bit smelly, the gannet colonies are really a wonder to behold. They are an incredible cacophonous swirling multitude, watching them I couldn’t quite work out how they don’t crash into each other above the colonies, with all the thousands of birds swooping, soaring, landing and taking off. Gannets are the supreme aerial hunter of the North Atlantic. Pale of eye, with razor sharp steel beaks, they can suddenly plunge into a death-defying dive that takes the breath away. They silently soar aloft, then do a slight turn, before plunging down and hitting the water at 80 feet per second or nearly 90km/h. To do this they have specifically developed neck muscles and a spongy bone plate at the base of their bill to reduce the impact. They also have special membranes to protect their eyes. If you witness such a dive close up, it is unforgettable.

As a species they are Amber Listed. In addition to the two colonies on the Saltee Islands, there is another colony on Bull Rock off the coast of Cork, and a small one on Ireland’s Eye off the coast of Dublin. The largest colony is on Little Skellig, where around 20,000+ nests are recorded, adding their deadly grace and cacophony to that otherworldly place.

Gannet • Great Saltee Island

Guillemots | Foracha

Guillemots • Great Saltee Island

Guillemots are the most common of Ireland’s auk species. They are very dark brown in colour with bright white breasts, and they can be easily mistaken for razorbills from a distance. Of all the flying birds, guillemots can dive the deepest. Plunging to an astonishing depth of over 200m (well over 600 feet). Though only the pupil of their eye is visible, the rest being covered by feather and skin, relative to their size they have enormous eyes. If humans had eyes of the same proportion they’d be as big as grapefruits. Those eyes allow the guillemot to zero in on prey from enormous distances, and to see in the deep depths of the cold ocean.

Unlike the plunging gannets, guillemots dive from sitting on the surface of the ocean, using their wings and feet to swim and strive downwards. They can stay under water for more than four minutes at a time. They can be long-living, with some individuals known to be over 40 years old. They are Amber Listed for conservation status. The colony here on the Great Saltee Island is the biggest with approximately 20,000 birds, with other notable colonies on the Cliffs of Moher, Horn Head in Donegal and Loop Head in County Clare.

Razorbills | Crosán

Razorbills • Great Saltee Island

Like the puffins and the guillemots, razorbills belong to the auk family. They look quite similar to guillemots from a distance – the easiest way to tell them apart is the razorbill’s heavier beak, compared to the more needle-like beak of the guillemot.

Razorbills are Amber Listed for conservation status. As well as here on the Great Saltee Island you can also see them on Rathlin Island, Horn Head in Donegal, the Cliffs of Moher, and Howth Head in County Dublin. They are the closest living relatives to the now extinct Great Auk, the largest seabird to have ever lived in the northern hemisphere. Great auks were hunted to extinction for their quantity of feathers, their meat and their oil. The last died in the mid-19th century.

Razorbills • Great Saltee Island

Great Black-Backed Gull | Droimneach Mór

Great Black-Backed Gull • Great Saltee Island

The apex predator of the islands, the Great Black-Backed Gull rules the roost on the Great Saltee Island. These birds are big and it is quite the experience to have them swooping low over you as you walk along near the cliffs of the island. They feed upon fish (often stolen from other birds), carrion and occasionally, other birds and their chicks, particularly some of the puffins and razorbills. All the other birds keep a wary eye out when a black-backed gull is nearby.

Black-backed gulls are of Amber Listed conservation status, and the Saltee Islands is an important home and refuge for these rulers of sea and sky. The largest colonies can be found on Inishmurray off the Coast of Sligo and Lambay Island off the coast of Dublin.

Kittiwake | Saidhbhéar

Kittiwake • Great Saltee Island

Kittiwakes are one of the smaller gulls, and named after their onomatopoeic call, that echoes in cacophony all along the cliffs of the island kitty waaakk kittywaakk. They are incredibly graceful fliers, with snow white bodies and heads, pale grey backs and wings that end in black tips. They nest in seemingly the most uncomfortable parts of the cliff face, clinging on to tiny projections in the rock. They were once terribly persecuted for sport in the 19th century, when it was in vogue to shoot seabirds on the wing, with thousands being killed at a time. This was often just for fun, though there was also a market for their snow white feathers for ladies hats.

Today they are widely spread across the world, but Kittiwakes are of Amber Listed conservation status in Ireland. They can be found on most headlands around the Irish Coast, with the largest colony at the Cliffs of Moher.

Kittiwake • Great Saltee Island

Cormorant | Broigheall

Cormorant • Great Saltee Island

Certain birds carry more of their dinosaur inheritance than others, and cormorants and shags are certainly primeval in appearance and movement. Unlike some of their seabird neighbours, they don’t travel long distances to fish in deeper waters. Instead they stay close to shore, swimming down with big webbed feet. Their appearance has led to them often being targeted for destruction.

As well as being persecuted by fishermen over the centuries, cormorants have often been treated rather unfairly in literature, writers like Aristophanes, Chaucer, Plutarch and Shakespeare have identified them with dark deeds, malevolence and greed. In Milton’s Paradise Lost, Satan takes the form of a cormorant:

‘Up he flew, and on the Tree of Life,

The middle Tree and highest there that grew,

Sat like a Cormorant; yet not true Life

Thereby regain’d, but sat devising Death

To them who liv’d.

Cormorants are Amber Listed for conservation status. As well as the Saltee Islands, they can be seen along the south and north-western coasts and they can also occasionally be seen inland along waterways.

Oystercatcher | Roilleach

Oystercatcher • Great Saltee Island

You’ll certainly hear oystercatchers before you see them. Their high pitched beepy call is almost ever-present near the small gannet colony. They are notable for their bright orangey-red feet, beak and eyes, with black head and wings and white underside. As their name suggests, these waders feed on shellfish and molluscs, though they can often be seen pacing around on the island as they hunt for worms and invertebrates.

Oystercatchers are Amber Listed for conservation status.

Oystercatcher • Great Saltee Island

Explore more sites in Ireland’s Ancient East