The Rock of Dunamase

An extraordinary landmark, the Rock of Dunamase towers over the plains of Laois. Strategically located, the Rock would have had commanding views of the landscape that provided formidable natural defenses. The position of this site may have been marked on a map by the Greek astronomer, mathematician and geographer Claudius Ptolemy in the second century AD. He appears to have labelled the site as Dunum, but thus far, no archaeological evidence dating to this early period has been discovered on the Rock of Dunamase.

The earliest evidence of a fort at the Rock of Dunamase dates to the early medieval period. The remains of a drystone wall thought to date to this time can be found just north of the gatehouse on the site. During this early stage the site was known as Dún Masc and it is recorded in the Annals of Ireland that Vikings raided the site in AD 844. They managed to fight their way past the defences and killed the abbot of Terryglass who was seeking shelter inside the fort.

The site was refortified after the Anglo-Norman invasions of Ireland. Dunamase was part of the dowry paid by the King of Leinster, Diarmait MacMurchada, when his daughter Aoife married Richard de Clare (Strongbow), the leader of the Norman invasions. Strongbow may have appointed Geoffrey de Constentin to fortify the site, some time in the 1170s. However, by 1181, Meiler FitzHenry had been ordered to hold the castle, which was on the dangerous and unsettled borderland with powerful Irish tribes. The famous chronicler Giraldus Cambrensis, who was a first-hand witness to the early days of the Norman invasion, described FitzHenry as, ‘a dark man with black, stern eyes and keen face … he was very strong, with a square chest … was high-spirited, proud, and brave to rashness.’

Meiler gained respect from both friend and foe for his bravery and daring in combat. In one famous exploit recounted by Giraldus, FitzHenry found himself deep in a forest, cut off from his men and surrounded by Irish warriors. He fought his way out and arrived back safe to find that his horse had been wounded by three Irish axes and two more axes were embedded in his shield, testament to the ferocity of the fighting.

FitzHenry was seen as the perfect man to hold the fiercely contested border lands of Laois. His valour saw him being given the honour of becoming Justiciar of Ireland. He constructed Dublin Castle in 1204, but Meiler regularly quarrelled with the other powerful Norman lords. In particular, Meiler FitzHenry became highly disgruntled when Dunamase was given to William Marshal as part of the dowry Marshal received upon marrying de Clare’s daughter, Isabella. It was Marshal that continued the work begun by de Constentin and FitzHenry, and who transformed Dunamase into a truly formidable fortress.

For practical information about visiting this site Click Here

An extraordinary landmark, the Rock of Dunamase towers over the plains of Laois. Strategically located, the Rock would have had commanding views of the landscape that provided formidable natural defenses. The position of this site may have been marked on a map by the Greek astronomer, mathematician and geographer Claudius Ptolemy in the second century AD. He appears to have labelled the site as Dunum, but thus far, no archaeological evidence dating to this early period has been discovered on the Rock of Dunamase.

The earliest evidence of a fort at the Rock of Dunamase dates to the early medieval period. The remains of a drystone wall thought to date to this time can be found just north of the gatehouse on the site. During this early stage the site was known as Dún Masc and it is recorded in the Annals of Ireland that Vikings raided the site in AD 844. They managed to fight their way past the defences and killed the abbot of Terryglass who was seeking shelter inside the fort.

The site was refortified after the Anglo-Norman invasions of Ireland. Dunamase was part of the dowry paid by the King of Leinster, Diarmait MacMurchada, when his daughter Aoife married Richard de Clare (Strongbow), the leader of the Norman invasions. Strongbow may have appointed Geoffrey de Constentin to fortify the site, some time in the 1170s. However, by 1181, Meiler FitzHenry had been ordered to hold the castle, which was on the dangerous and unsettled borderland with powerful Irish tribes. The famous chronicler Giraldus Cambrensis, who was a first-hand witness to the early days of the Norman invasion, described FitzHenry as, ‘a dark man with black, stern eyes and keen face … he was very strong, with a square chest … was high-spirited, proud, and brave to rashness.’

Meiler gained respect from both friend and foe for his bravery and daring in combat. In one famous exploit recounted by Giraldus, FitzHenry found himself deep in a forest, cut off from his men and surrounded by Irish warriors. He fought his way out and arrived back safe to find that his horse had been wounded by three Irish axes and two more axes were embedded in his shield, testament to the ferocity of the fighting.

FitzHenry was seen as the perfect man to hold the fiercely contested border lands of Laois. His valour saw him being given the honour of becoming Justiciar of Ireland. He constructed Dublin Castle in 1204, but Meiler regularly quarrelled with the other powerful Norman lords. In particular, Meiler FitzHenry became highly disgruntled when Dunamase was given to William Marshal as part of the dowry Marshal received upon marrying de Clare’s daughter, Isabella. It was Marshal that continued the work begun by de Constentin and FitzHenry, and who transformed Dunamase into a truly formidable fortress.

For practical information about visiting this site Click Here

The Rock of Dunamase • Laois

The Defences of the Rock of Dunamase and Later History

The castle had a series of strong defensive features that made use of the unusual natural topography. The remains of the Outer Barbican appear as a large ditch that surrounds the base of the hill. It was originally roughly triangular in plan, and would have featured a strong wooden palisade and earthworks behind the ditches to form an impressive first line of defence.

A barbican gate now stands isolated on the path, just above the remnants of a deep ditch. The gate has a number of defensive features, such as murder holes and a slot for a portcullis. It gave access into the Inner Barbican, where attackers would have to overcome steep ditches and tall stone walls. The walls feature fighting platforms and wall-walks, from where archers could have rained arrows down upon the enemy.

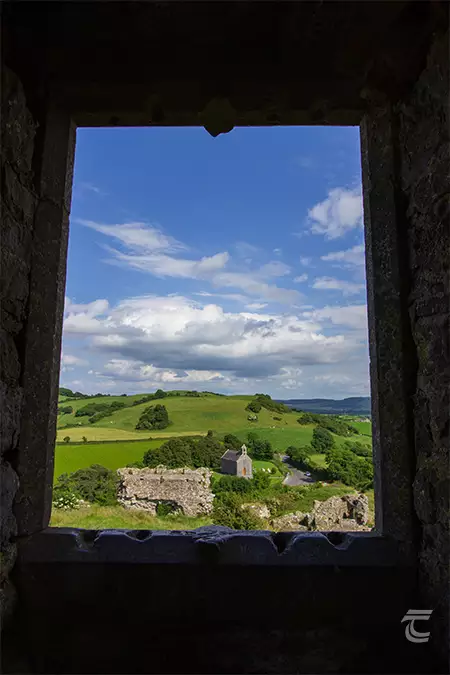

The twin-towered gatehouse gave access into the Lower Ward. This area had a number of buildings, including accommodation for the troops and essential facilities such as forges and blacksmiths’ workshops to ensure the weapons and armour were well maintained. The Upper Ward was once separated from the Lower by a stone wall, which has since been demolished. The Upper Ward was the heart of the fortress, and housed the most important structure on the site, the Great Hall. From this vantage point you can enjoy stunning views over the rolling countryside of County Laois.

The Great Hall may have been one of the first things constructed by the Anglo-Normans. Professor Tadhg O’Keeffe suggests it may be contemporary with the great donjon (or keep) of Trim Castle. It began as a rather simple building, though it has been changed throughout the centuries.

Interior of the Castle • Laois

The castle came into the possession of Roger Mortimer, when he married William Marshal’s granddaughter, Maud de Braose, in c.1247. Though we tend to hear more about men than women in medieval sources, it appears that Maud was a highly respected and powerful figure in her own right, and every bit as brave and cunning as her famous grandfather. During the Second Barons’ War, she was a key supporter of King Henry III. It was Maud herself who devised a plan for the escape of Prince Edward after he had been taken hostage by Simon de Montfort. Maud and Roger were a formidable pair. It was Roger Mortimer who killed de Monfort himself, and he sent de Montfort’s head and genitals back to Maud as a gift. I think the modern term ‘power couple’ would be an understatement.

However the Mortimer reign at Dunamase was to come to an ignoble end. Their grandson, Roger Mortimer, 1st Earl of March, became entangled in a conspiracy ending in the deposition and death of King Edward II. He briefly ruled with Queen Isabella, but when King Edward III came to power he took revenge for his father’s humiliation. He had Roger Mortimer executed. He was hung at Tyburn in 1330. His body suspended from the gallows for two days and nights in full view of the populace. The Mortimer family lost Dunamase along with all their other holdings, which were all forfeited to the King.

Through the 14th century Anglo-Norman control in the midlands began to weaken and crumble under the relentless pressure of the local O’Mordha clan. The O’Mordhas finally managed to seize Dunamase in the 1330s, but they left the site unoccupied. The castle then fell into disrepair and then much of the fortress was deliberately destroyed, often attributed to Colonel Hewson, one of Oliver Cromwell’s officers during his invasion of Ireland in the 17th century, although no records of this survive in Cromwell’s accounts and the damage may have occurred much later.

Evidence of the final destruction of Dunamase can be found near the gatehouse. There you can find a small lime kiln, that probably dates to the 19th century. The stones were taken from the walls and heated in kilns like this by local farmers to create unslaked lime, which was then added to the fields to help to neutralize the acidity of the soil and increase fertility. So piece by piece this once mighty stronghold was broken down leaving only the echoes of its greatness that we find today.

You can hear the full story of the Rock of Dunamase in our free audio guide, produced for Laois County Council. Available on your favourite podcast platform, see here.

Upper left: ruins of the Castle at the Rock of Dunamase • Lower left: the barbican gate • Right: commanding views over the Laois countryside

Top: ruins of the Castle at the Rock of Dunamase • Middle: commanding views over the Laois countryside • Bottom: the barbican gate