The Rock of Cashel

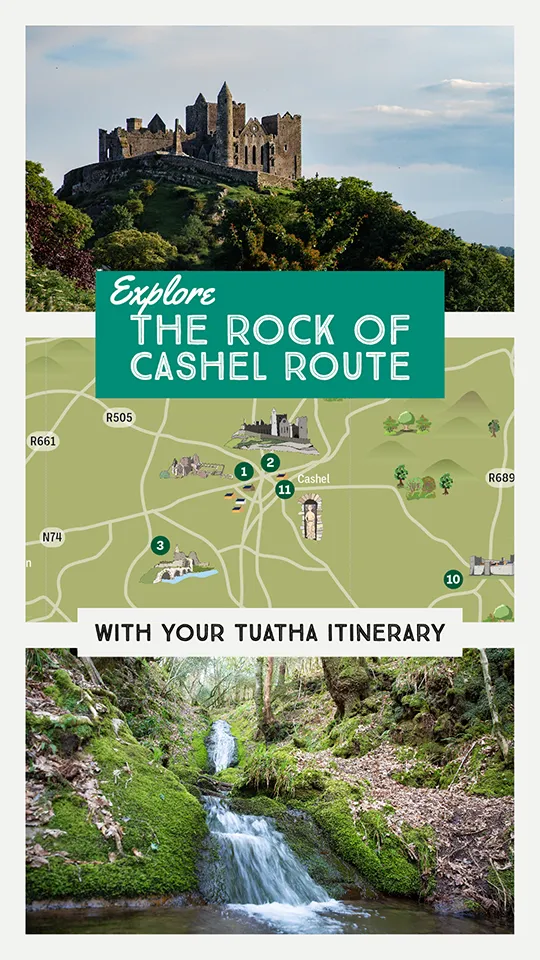

The Rock of Cashel, or in Irish Carraig Phádraig [translating to St. Patrick’s Rock], is undoubtedly one of Ireland’s most iconic monuments. We have to admit to a little bias here, given that the Rock of Cashel is one of our local monuments, but it absolutely deserves all the attention it receives. It dominates the skyline as you approach Cashel, as it perches majestically on a high stony outcrop overlooking the fertile green plains of South Tipperary, some of the best land in the country. It’s so easy to be so impressed by the large stone buildings and the grandeur of the place that you overlook the wonderful small hidden details, like the characterful decorative flourishes in the Cathedral, the sculpture of the medieval tombs, or the delicate and ephemeral traces of pigment that once formed colourful frescoes in Cormac’s Chapel. We hope this short overview might inspire you to dwell a little longer, look a little closer and dig a little deeper into the story of this magnificent site.

The Rock of Cashel is quite often mistakenly called Cashel Castle, when it isn’t a castle in the true sense at all. In fact, all the buildings that you see on the Rock today are ecclesiastical. However, it is also known as Cashel of the Kings and that is a more accurate name. The Rock was originally home to the Eóganachta, who were once Kings of Munster. After a series of wars, they lost the lands in the late 10th century to their great rivals the Dál Cais, who became the preeminent dynasty of Munster. Brian Boru was perhaps the most famous of this line. He became King of Cashel in AD 978, and went on to become the most famous of the High Kings of Ireland, until his death in the aftermath of the Battle of Clontarf in 1014. Brian’s great grandson, Muircheartach Ua Briain changed the destiny of the Rock of Cashel forever when he granted it to the Church in 1101. Rather than being solely an act of spiritual generosity, it was also a shrewd political move, as it ensured the Eóganacht could never reclaim their ancient royal seat. However, it was not long before the Eóganacht influence returned to the Rock of Cashel. Cormac Mac Cárthaigh (a member of the Eóghanact and King of Munster) became the patron of the most spectacular building on the site, Cormac’s Chapel. You can hear more about the early history of the Rock of Cashel in this episode of our Amplify Archaeology Podcast with Dr. Patrick Gleeson.

The Rock of Cashel was notoriously attacked during the Irish Confederate Wars in 1647, when Murrough O’Brien (known as Lord Inchiquin) marched into Cashel on behalf of the English Parliament. It is said that the townspeople fled to the cathedral of the Rock for protection, but Inchiquin and his men stormed the place, slaughtering hundreds (some estimate 3,000) townspeople and clergy.

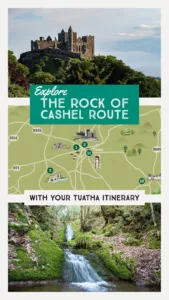

This ancient royal and ecclesiastical complex became a protestant place of worship later in the 17th century. The Archbishop continued to live on site until the time of Archbishop Arthur Price in the mid-18th century. When St John’s Cathedral and a new residence for the Archbishop was constructed in the town, the Rock was finally abandoned. It began to fall into decay until it was taken into state care in the 1870s. This is a place absolutely filled with stories and splendour, when you are finished exploring here don’t miss out on visiting Hore Abbey, a short walk away below the Rock. And if you’re looking to discover even more of the medieval marvels of Tipperary, try our Rock of Cashel Route, a road trip itinerary that will lead you to sprawling abbeys, secret sites, holy wells and hidden waterfalls.

For practical information about visiting this site Click Here

The Rock of Cashel, or in Irish Carraig Phádraig [translating to St. Patrick’s Rock], is undoubtedly one of Ireland’s most iconic monuments. We have to admit to a little bias here, given that the Rock of Cashel is one of our local monuments, but it absolutely deserves all the attention it receives. It dominates the skyline as you approach Cashel, as it perches majestically on a high stony outcrop overlooking the fertile green plains of South Tipperary, some of the best land in the country. It’s so easy to be so impressed by the large stone buildings and the grandeur of the place that you overlook the wonderful small hidden details, like the characterful decorative flourishes in the Cathedral, the sculpture of the medieval tombs, or the delicate and ephemeral traces of pigment that once formed colourful frescoes in Cormac’s Chapel. We hope this short overview might inspire you to dwell a little longer, look a little closer and dig a little deeper into the story of this magnificent site.

The Rock of Cashel is quite often mistakenly called Cashel Castle, when it isn’t a castle in the true sense at all. In fact, all the buildings that you see on the Rock today are ecclesiastical. However, it is also known as Cashel of the Kings and that is a more accurate name. The Rock was originally home to the Eóganachta, who were once Kings of Munster. After a series of wars, they lost the lands in the late 10th century to their great rivals the Dál Cais, who became the preeminent dynasty of Munster. Brian Boru was perhaps the most famous of this line. He became King of Cashel in AD 978, and went on to become the most famous of the High Kings of Ireland, until his death in the aftermath of the Battle of Clontarf in 1014. Brian’s great grandson, Muircheartach Ua Briain changed the destiny of the Rock of Cashel forever when he granted it to the Church in 1101. Rather than being solely an act of spiritual generosity, it was also a shrewd political move, as it ensured the Eóganacht could never reclaim their ancient royal seat. However, it was not long before the Eóganacht influence returned to the Rock of Cashel. Cormac Mac Cárthaigh (a member of the Eóghanact and King of Munster) became the patron of the most spectacular building on the site, Cormac’s Chapel. You can hear more about the early history of the Rock of Cashel in this episode of our Amplify Archaeology Podcast with Dr. Patrick Gleeson.

The Rock of Cashel was notoriously attacked during the Irish Confederate Wars in 1647, when Murrough O’Brien (known as Lord Inchiquin) marched into Cashel on behalf of the English Parliament. It is said that the townspeople fled to the cathedral of the Rock for protection, but Inchiquin and his men stormed the place, slaughtering hundreds (some estimate 3,000) townspeople and clergy.

This ancient royal and ecclesiastical complex became a protestant place of worship later in the 17th century. The Archbishop continued to live on site until the time of Archbishop Arthur Price in the mid-18th century. When St John’s Cathedral and a new residence for the Archbishop was constructed in the town, the Rock was finally abandoned. It began to fall into decay until it was taken into state care in the 1870s. This is a place absolutely filled with stories and splendour, when you are finished exploring here don’t miss out on visiting Hore Abbey, a short walk away below the Rock. And if you’re looking to discover even more of the medieval marvels of Tipperary, try our Rock of Cashel Route, a road trip itinerary that will lead you to sprawling abbeys, secret sites, holy wells and hidden waterfalls.

For practical information about visiting this site Click Here

The iconic Rock of Cashel • Tipperary

Cormac’s Chapel

Cormac’s Chapel is one of the most spectacular stone buildings in Ireland. It was consecrated in 1134, and it bears the name of Cormac Mac Cárthaig, King of Munster. The chapel has strong connections to Germany. A number of visits of Benedictine monks from Ratisbon in Bavaria were recorded during the period of its construction between c.1127–1134, and the form of the chapel is similar in some respects to that of the Church of St. James in Regensburg. It is likely (as indicated by the name as well as its form), that this building served as a royal chapel for the glorification of King Cormac in life and death.

In a number of respects, Cormac’s Chapel is an unusual building, especially with the two stone towers. The building has two-storeys with vaulted ceilings and an external stone roof. The floors are connected by a spiral stairs in the southern tower. The whole building is elaborately decorated in the Hiberno-Romanesque architectural style. The chapel is particularly notable for the frescoes on the walls and ceiling of the choir. The architect or master masons who built Cormac’s Chapel, may also be responsible for the wonderful church at Kilmalkedar in the Dingle Peninsula.

Some of the key features of Cormac’s Chapel • Rock of Cashel

The challenges of the preservation of the frescoes led to the chapel being covered in scaffolding for many years, and the restricted ticketed system of entry into the chapel. These measures help to reduce the humidity and moisture in the air which poses a threat to the survival of the paintings. The earliest dates to 1134 and it is a very simple design, however the bulk of fresco work was carried out in c.1170. The scene that is depicted on the roof is thought to be the Adoration of Christ. The colours are derived from minerals and pigments, some from exotic and expensive sources – for example the use of the blue colour on the ceiling was derived from Lapis Lazuli (a mineral likely to have been imported from Afghanistan). During its heyday the bright colours must have been an astonishing sight.

The large sarcophagus at the rear of Cormac’s Chapel is beautifully carved with Hiberno-Norse Urnes-style decoration. It is thought to date to the 12th century, and archaeologist John Bradley believed it may have been the resting place of Tadhg Mac Cárthaig, King of Munster (and elder brother of Cormac) who died in 1124. The tomb was moved inside Cormac’s Chapel in the 19th century, and it may have originally stood in a now lost chapel or church.

For me, Cormac’s Chapel is the most spectacular example of Hiberno-Romanesque architecture in Ireland. When you visit, you can see many of the hallmark features of this flamboyant architectural style; particularly the round-arched doorways with decorated tympanums the northern door with a depiction of a centaur battling a lion, the southern door with another beast (possibly a lion though it looks more like a hippo or rhino). Blind arcading is another key feature of the Hiberno-Romanesque, along with the elaborate chancel arch with its numerous heads (perhaps depicting saints or religious figures, abbots, masons or benefactors), delicate frescoes and decorative sculptural features like chevrons, zig-zags and floral and animal depictions. It is a feast for the eyes!

St. Patrick’s Cross

St. Patrick’s Cross • Rock of Cashel

According to Professor Tadhg O’Keeffe, there is the distinct possibility that the cross was commissioned by the famous Cormac Mac Cárthaig, King of Munster as part of his patronage of the site. It is unusual in some respects to the more typical Irish high cross with the surviving arm supported by an upright strut. The cross depicts Christ on one side, and a bishop on the other. The base has an unusual design that Peter Harbison has identified as a labyrinth and minotaur. It has been suggested that the depiction of Christ is modelled on the Volto Santo wooden crucifix from Lucca in Italy, indicating ideas of European influences and pilgrimage. The original cross can be seen in the Vicar’s Choral where it is safe from weathering with an excellent replica on site. When the Gothic cathedral was being constructed, the high cross was moved from its original location near Cormac’s Chapel and placed where the replica stands today.

The Cathedral

The Cathedral • Rock of Cashel

The Cathedral is the largest building on the Rock and dates to around the 13th century. It is almost unique as the nave is considerably shorter than the chancel; a bishop’s tower built onto the end of the nave shortens it even further. The cathedral contains a myriad of medieval sculptures; a number of carved heads can be seen high on the capitals, and grave slabs and tomb niches can also be seen throughout. One of the most famous graves is that of Miler Magrath (d. 1622). He was Archbishop of Cashel and was notorious for controversy and corruption.

The tower at the end of the nave dates to the fifteenth century. It served as a home for the Archbishop of Cashel. From the tower the Archbishop could access the intramural passageways that extend throughout the upper floors of the cathedral.

The Cathedral • Rock of Cashel

The Round Tower

The Round Tower • Rock of Cashel

It is believed that the Round Tower dates to the early 12th century, and is likely to have been built shortly after Muirchertach donated the site to the church in 1101, perhaps it was one of the first stone buildings on the Rock. It is a fine example, with an architraved round arched doorway with semi-ashlar masonry. At approximately 28 metres [92 feet] tall, the round tower would have soared above the other buildings until the Gothic cathedral was constructed. The tower would have acted as a potent symbol of the Christian community at the Rock of Cashel.

The Vicar’s Choral

The Vicar’s Choral • Rock of Cashel

The Hall of the Vicars Choral was the last building to be constructed on the Rock. It housed the choir that served the cathedral. Restored and renovated in the 1980s, its undercroft houses a number of artefacts from the Rock and its locality, including the original St Patrick’s Cross. High on the south-eastern exterior wall of the Vicars Choral is a sheela-na-gig.

The Vicar’s Choral • Rock of Cashel

Upper left: aerial view of the Rock of Cashel • Lower left: an Urnes-style sarcophagus • Right: the famous site overlooking Cashel

Top: aerial view of the Rock of Cashel • Middle: the famous site overlooking Cashel • Bottom: an Urnes-style sarcophagus

The Rock of Cashel Visitor Information

For more than a thousand years, the Rock of Cashel has been a site of incredible significance. It is immense, majestic, even intimidating, yet is also filled with wonderful little hidden details. Each visit can reveal something new!

Explore more sites in Ireland’s Ancient East