The Hill of Tara

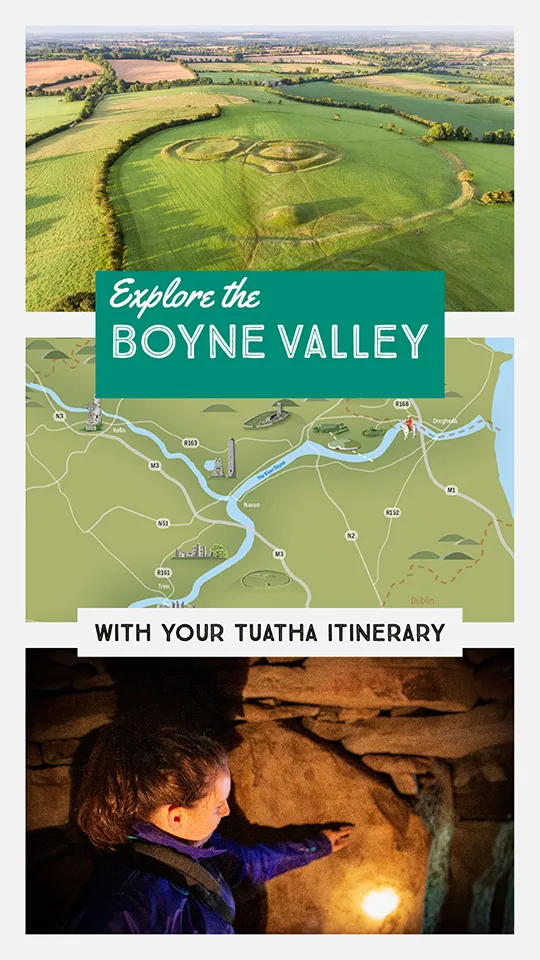

The Hill of Tara has been a place of significance for millennia of Irish history, with a complex concentration of monuments and significant events that cover a span of time from approximately 3500 BC to the 19th century. It is one of the most important archaeological sites in Ireland, and indeed the world. Though some people can feel a little underwhelmed on their first visit to Tara. As the majority of Tara’s buildings would have been constructed from timber, the site appears today as a series of undulating earthworks and grassy banks and ditches. It can be a little difficult on first viewing to get a true sense of the phenomenal concentration of archaeology on the Hill of Tara, and the site certainly requires the visitor to use their imagination. However, at such an evocative and atmospheric place, it is not hard to conjure visions of ancient temples, palaces and tombs. Tara is a place where there is only a thin veil between archaeology and mythology, history and legend.

The name Tara is thought to derive from either the Irish word Temair meaning ‘a great height’, or a derivative of the Greek temenos or Latin templum meaning ‘a sacred space’. Both of these meanings perfectly suit the Hill of Tara, once described as ‘probably the most consecrated spot in Ireland’. Many of the names of the individual monuments on the Hill of Tara come from Dindshenchas Éireann (‘Lore of the Place Names of Ireland’), which was compiled in the 11th century. As they were recorded centuries after the initial use of the monuments, these descriptions must be taken with a pinch of salt, however they add to the folkloric mystique of this most enigmatic of Irish landscapes. Indeed most of the early texts on Tara tell us more about the medieval context and society in which they were written rather than ancient lore or traditions of Tara.

As well as being a place of ancient kings and legends, The Hill of Tara was also the setting for more recent drama. One of the key battles of Ireland’s 1798 Rebellion took place there, with more than four thousand United Irishmen making an unsuccessful stand against a militia of British yeomanry at the Battle of Tara Hill. Over 350 rebels were killed. Two memorials mark their memory. A Celtic Cross and gravestone, and a stone, said to be the Lia Fail, The legendary Stone of Destiny, was moved a short distance to mark their supposed burial place. In 1843, Daniel O’Connell drew on the symbolic power of Tara in the national consciousness when he held a ‘Monster Rally’ that called for the Repeal of Ireland’s Union with Britain, attended by a crowd that numbered over a million people.

For practical information about visiting this site Click Here

The Hill of Tara has been a place of significance for millennia of Irish history, with a complex concentration of monuments and significant events that cover a span of time from approximately 3500 BC to the 19th century. It is one of the most important archaeological sites in Ireland, and indeed the world. Though some people can feel a little underwhelmed on their first visit to Tara. As the majority of Tara’s buildings would have been constructed from timber, the site appears today as a series of undulating earthworks and grassy banks and ditches. It can be a little difficult on first viewing to get a true sense of the phenomenal concentration of archaeology on the Hill of Tara, and the site certainly requires the visitor to use their imagination. However, at such an evocative and atmospheric place, it is not hard to conjure visions of ancient temples, palaces and tombs. Tara is a place where there is only a thin veil between archaeology and mythology, history and legend.

The name Tara is thought to derive from either the Irish word Temair meaning ‘a great height’, or a derivative of the Greek temenos or Latin templum meaning ‘a sacred space’. Both of these meanings perfectly suit the Hill of Tara, once described as ‘probably the most consecrated spot in Ireland’. Many of the names of the individual monuments on the Hill of Tara come from Dindshenchas Éireann (‘Lore of the Place Names of Ireland’), which was compiled in the 11th century. As they were recorded centuries after the initial use of the monuments, these descriptions must be taken with a pinch of salt, however they add to the folkloric mystique of this most enigmatic of Irish landscapes. Indeed most of the early texts on Tara tell us more about the medieval context and society in which they were written rather than ancient lore or traditions of Tara.

As well as being a place of ancient kings and legends, The Hill of Tara was also the setting for more recent drama. One of the key battles of Ireland’s 1798 Rebellion took place there, with more than four thousand United Irishmen making an unsuccessful stand against a militia of British yeomanry at the Battle of Tara Hill. Over 350 rebels were killed. Two memorials mark their memory. A Celtic Cross and gravestone, and a stone, said to be the Lia Fail, The legendary Stone of Destiny, was moved a short distance to mark their supposed burial place. In 1843, Daniel O’Connell drew on the symbolic power of Tara in the national consciousness when he held a ‘Monster Rally’ that called for the Repeal of Ireland’s Union with Britain, attended by a crowd that numbered over a million people.

For practical information about visiting this site Click Here

Sunrise over the Hill of Tara • Meath

Key Features of the Hill of Tara

Map of the Hill of Tara • Meath

St. Patrick’s Church

St Patrick’s Church, the Hill of Tara • Meath

Inside the 19th century church (now the visitor centre), there is a beautiful stained-glass window by artist Evie Hone, and an informative audiovisual presentation that tells the story of Tara. The churchyard has a number of historic features, including two standing stones, known in legend as Bloc and Bligne (pictured), which are said to have played a part in the royal inauguration ceremonies. The taller stone, Bligne, has a sheela-na-gig near the base, though it can be difficult to see due to weathering and lichen growth. This larger stone is also known as Adomnán’s Cross, after St. Adomnán the Abbot of Iona and biographer of St. Colmcille.

Just outside the churchyard the statue of St Patrick reflects the legend of Patrick lighting the Easter Fire on the nearby Hill of Slane in AD 433.

The Banqueting Hall

The Banqueting Hall • Meath

The Banqueting Hall, or Tech Midchúarta (meaning the House of the Mead Circuit), certainly has one of the most evocative names on the hill. It appears in the Dindgnai Temrach that dates to around AD 1000. ‘It is in the form of a long house…it is said that it was here that the Feis Temro was held, which seems true; because as many men would fit in it as would form the choice part of the men of Ireland. And this was the great house of a thousand warriors’. Despite this evocative picture, it is more likely that the Banqueting Hall was a processional routeway perhaps used during ritual or inauguration ceremonies. The twin earthworks block the view as one walks up the slope, with occasional gaps that appear to focus on key features in the landscape. It may be as early as the Neolithic period in date, as it is similar to other cursus monuments, and appears to be aligned with the Mound of the Hostages on the summit.

The Banqueting Hall • Meath

Ráith na Rí

Ráith na Rí • Meath

The great enclosure of Ráith na Rí (meaning ‘the King’s Fort) was first constructed during the Iron Age, in around 100 BC. Seen from above, the enclosure is oval in shape with a circumference of approximately 1km, incorporating many of the main features of the Hill of Tara. The enclosure is formed by a deep ditch with an external, rather than internal, bank, with a wooden palisade. This suggests the enclosure is more symbolic than defensive.

Human remains, including an infant burial, artefacts and animal bones were found in the fill of the ditch during archaeological excavations by the Discovery Programme. The infant, thought to be around 6 months old, was found buried with a dog. It has been interpreted that the dog may have been a spiritual guardian for the child’s journey into the Otherworld.

The Rath of the Synods

The Rath of the Synods • Meath

The Rath of the Synods is a quadravallate (meaning four-ditched) enclosure, that appears as a particularly bumpy area near the churchyard. It takes its name from its association with significant religious assemblies [known as synods] presided over by important ecclesiastical figures. Archaeological evidence shows just how important the Rath of the Synods once was, with the discovery of sherds of Roman pottery and fragments of glass from the highest quality imported Roman tableware. This demonstrates the tastes, fashion and trade links of Ireland’s elite, and their trading connections to Roman Britain and beyond.

This monument was badly damaged when a group called the ‘British Israelites’ dug in search of the Ark of the Covenant between 1899 and 1902. Their destruction of this hugely important site did not go uncontested, and a protest campaign led by figures like Maud Gonne, Douglas Hyde, W.B. Yeats, George Moore and Arthur Griffith eventually forced the works to stop.

The Rath of the Synods • Meath

The Mound of the Hostages

The Mound of the Hostages • Meath

The oldest visible monument on the Hill of Tara is the Mound of the Hostages (Duma na nGiall). It is a Neolithic passage tomb, dating to over 5,000 years old, though it continued to be an important place of burial and ritual for many centuries after its first construction. Archaeological investigations revealed over 300 individuals interred in and around the tomb over a period from 3400BC to 1600BC. When the Mound of the Hostages was excavated in the 1950s, the chamber of the Neolithic tomb with a rich assemblage of artefacts and human remains was discovered. The dig also revealed that the earthen mound was used as a cemetery in the Bronze Age. One of these burials, the very last to be inserted into the mound, was that of a young teenager. He was found buried with a necklace made of exotic stones and beads, and was, perhaps, one of the ‘hostages’ from which the tomb takes its name. The results of the excavation are detailed in a fantastic publication by Professor Muiris O’Sullivan, and you can see the artefacts in a dedicated exhibition in the National Museum of Ireland on Kildare Street, Dublin.

The Lia Fáil

The Lia Fáil • Meath

Today the Forradh is topped with a standing stone, said to be the Lia Fáil (Stone of Destiny), which legend said would cry out when the rightful King of Ireland placed his foot upon it (the stone must be the wrong one, or broken because it didn’t make a peep when I tried it). The story of the Lia Fáil comes from the Dindgnai Temrach, that placed it originally to the north of the Mound of the Hostages. It was moved to the top of the Forradh in 1824.

Another story claims that the true Lia Fáil is the Stone of Scone in Scotland. This comes from both Scottish chroniclers, and the famous 16th century historian Geoffrey Keating, who’s History of Ireland is heavily laden with legend and folklore. The claim that the Stone of Scone and the Lia Fáil are one and the same was hotly disputed, in particular by Patrick Weston Joyce in 1911. Like many features on the Hill of Tara, mythology, fact, history and legend are all entwined in a knotty tangle.

The Lia Fáil • Meath

The Forradh

The Forradh • Meath

This distinctive mound is one of Tara’s most enigmatic monuments, as the date of its construction is uncertain, though it incorporates an earlier Bronze Age barrow monument. It is believed to have been the inauguration mound, which played a central role in the ceremonies of kingship during the early historic period. However, it is possible that the Forradh may have been a pre-Norman Irish motte-style castle, as discussed by Professor Tadhg O’Keeffe in this episode of the Amplify Archaeology.

Interestingly, there was another mound similar to the Forradh that has been lost. It was known as Duma na mBó (possibly translating to the Mound of the Cows). The famous antiquarian George Petrie described it in the 19th century as being 6 feet high and forty feet in diameter. In 1901, it was noted that a local landowner had removed the mound to use the earth in an adjacent field. The Discovery Programme identified the location of Duma na Mbó in a geophysical survey.

Tech Chormaic (Cormac’s House)

Tech Chormaic • Meath

Adjoining the Forradh you can see the circular earthworks of Cormac’s House (Tech Chormaic). This is a large bivallate ringfort that is thought to date to the early medieval period. By conjoining the ringfort to the iconic Forradh within the sacred precinct of Tara, it is likely that the builder was sending a powerful political message. It is linked with the legendary Irish king Cormac mac Airt. It is possible that Cormac may have been a real historical figure, although he has become entwined with mythology and legend. He is said to have ruled from Tara for forty years during the Iron Age. He was famed for his wisdom and generosity. In the Annals of Clonmacnoise, translated in 1627, he is described as: ‘absolutely the best king that ever reigned in Ireland before himself … wise learned, valiant and mild, not given causelessly to be bloody as many of his ancestors were, he reigned majestically and magnificently’.

Tech Chormaic • Meath

Clóenfherta | The Sloping Trenches

Clóenfherta • Meath

The Sloping Trenches, or in Irish Clóenfherta, are associated with another legendary King of Tara; Lugaid mac Con. According to legend, Kings had to be perfect in form and judgement. Lugaid made a false judgement, and so part of his fort collapsed forming the Sloping Trenches. After such an inauspicious event, had to leave Tara and his Kingship behind.

Ráith Gráinne

Ráith Gráinne • Meath

Ráith Gráinne is a large ring-barrow, a burial monument typically dating to the Bronze or Iron Age. It is named after Gráinne, the daughter of the legendary King Cormac. She married the great warrior Fionn MacCumhaill on the Hill of Tara, but at the wedding feast in the Banqueting Hall she fell in love with Diarmuid, one of Fionn’s warriors. The young lovers eloped and fled across Ireland to avoid Fionn’s anger. So began one of the most tragic tales of ancient Ireland.

Ráith Gráinne • Meath

Upper left: the monumental landscape of the Hill of Tara • Lower left: one of the ‘Wishing Trees’, a rag tree, at Tara • Right: Professor Muiris O Sullivan leads a Tuatha Tour at the Hill of Tara

Top: the monumental landscape of the Hill of Tara • Middle: Professor Muiris O Sullivan leads a Tuatha Tour at the Hill of Tara • Bottom: one of the ‘Wishing Trees’, a rag tree, at Tara

Explore more sites in Ireland’s Ancient East