St Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin

St Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin, has played an influential role in the city’s complex and diverse story. The origins of the site appear to have been a holy well, said to have been used by Patrick himself in the 5th century. A late 8th century reference to St Patrick’s in insula (or St Patrick’s on an island) suggests that there was an early church on the site, that was presumably situated on a small island between two branches of the River Poddle. The presence of an early medieval church is supported by six stone grave slabs that appear to date to around the 10th century. However this location on the low-lying ground hasn’t always been appreciated, as an account from c.1841 describes: ‘Its situation, however is most objectionable, being built on the lowest ground in the city, and surrounded on every side with old narrow streets, of the meanest and filthiest description…’

In 1191 John Cumin, Dublin’s first Anglo-Norman archbishop, oversaw the creation of a collegiate establishment. This was a place where clergy could devote their time in equal measure to worship and study. The church was rededicated to God, the Blessed Virgin Mary and St Patrick in 1192. At this time it appears that while archbishop Cumin had enlarged or embellished the existing church, it wasn’t until the time of Cumin’s successor, the influential Archbishop Henry de Loundres, that work began the cathedral that we know today. In 1225 King Henry III gave protection to clergymen who begged and raised funds across Ireland to pay for the building. By 1254 the building was consecrated, suggesting that it was completed (or near completed) by that date. It was constructed in a cruciform shape in the English Gothic style, with its distinctive pointed arches, vaulted roofs, buttresses, large windows, and spires.

St Patrick’s Cathedral has been enlarged and modified multiple times throughout its long history. Some of these changes reflected the changing architectural tastes and styles of the contemporary archbishop or a patron. Though sometimes they were a response to calamity, such as in 1362 when the church was ‘damaged by fire due to the negligence of John the sexton’. One particularly beautiful addition was made in c.1270, when the Archbishop Falk de Saunford had the Lady Chapel built behind the high altar. In 1665 the Lady Chapel, was given over to Huguenot worship, and was renamed L’Eglise Française de St Patrick. It can still be seen today, surrounded by reminders of Huguenot life in the city, such as the Huguenot Bell, which is dedicated “To the glory of God and in the memory of the coming of the Huguenots to Dublin, 1685.” The Huguenots were Calvinist protestants, who had been forced to flee France to escape religious persecution in the 17th century. One of the prominent members of the Huguenots was Élie Bouhéreau, who became the first librarian of the nearby Marsh’s Library. This had been established by Archbishop Narcissus Marsh as Ireland’s first Public Library in 1707.

By the early 19th century, the cathedral was becoming increasingly dilapidated, with areas being declared unsafe to the public. To halt the decline, a major programme of reconstruction and renovation was carried out in the middle of the 19th century, funded by the wealthy brewery heir Sir Benjamin Lee Guinness, whose statue can today be seen outside the cathedral. His is just one of the many marvellous monuments in St Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin.

For practical information about visiting this site Click Here

St Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin, has played an influential role in the city’s complex and diverse story. The origins of the site appear to have been a holy well, said to have been used by Patrick himself in the 5th century. A late 8th century reference to St Patrick’s in insula (or St Patrick’s on an island) suggests that there was an early church on the site, that was presumably situated on a small island between two branches of the River Poddle. The presence of an early medieval church is supported by six stone grave slabs that appear to date to around the 10th century. However this location on the low-lying ground hasn’t always been appreciated, as an account from c.1841 describes: ‘Its situation, however is most objectionable, being built on the lowest ground in the city, and surrounded on every side with old narrow streets, of the meanest and filthiest description…’

In 1191 John Cumin, Dublin’s first Anglo-Norman archbishop, oversaw the creation of a collegiate establishment. This was a place where clergy could devote their time in equal measure to worship and study. The church was rededicated to God, the Blessed Virgin Mary and St Patrick in 1192. At this time it appears that while archbishop Cumin had enlarged or embellished the existing church, it wasn’t until the time of Cumin’s successor, the influential Archbishop Henry de Loundres, that work began the cathedral that we know today. In 1225 King Henry III gave protection to clergymen who begged and raised funds across Ireland to pay for the building. By 1254 the building was consecrated, suggesting that it was completed (or near completed) by that date. It was constructed in a cruciform shape in the English Gothic style, with its distinctive pointed arches, vaulted roofs, buttresses, large windows, and spires.

St Patrick’s Cathedral has been enlarged and modified multiple times throughout its long history. Some of these changes reflected the changing architectural tastes and styles of the contemporary archbishop or a patron. Though sometimes they were a response to calamity, such as in 1362 when the church was ‘damaged by fire due to the negligence of John the sexton’. One particularly beautiful addition was made in c.1270, when the Archbishop Falk de Saunford had the Lady Chapel built behind the high altar. In 1665 the Lady Chapel, was given over to Huguenot worship, and was renamed L’Eglise Française de St Patrick. It can still be seen today, surrounded by reminders of Huguenot life in the city, such as the Huguenot Bell, which is dedicated “To the glory of God and in the memory of the coming of the Huguenots to Dublin, 1685.” The Huguenots were Calvinist protestants, who had been forced to flee France to escape religious persecution in the 17th century. One of the prominent members of the Huguenots was Élie Bouhéreau, who became the first librarian of the nearby Marsh’s Library. This had been established by Archbishop Narcissus Marsh as Ireland’s first Public Library in 1707.

By the early 19th century, the cathedral was becoming increasingly dilapidated, with areas being declared unsafe to the public. To halt the decline, a major programme of reconstruction and renovation was carried out in the middle of the 19th century, funded by the wealthy brewery heir Sir Benjamin Lee Guinness, whose statue can today be seen outside the cathedral. His is just one of the many marvellous monuments in St Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin.

For practical information about visiting this site Click Here

St Patrick’s Cathedral, viewed from St Patrick’s Park • Dublin

The Monuments of St Patrick’s Cathedral

Some of the more than 200 monuments of St Patrick’s Cathedral • Dublin

One of the incredible features of St Patrick’s Cathedral is the wealth of monuments, statues and plaques within it. Among the many famous and influential names that jump out from the stones is that of the author and satirist, Jonathan Swift. Swift was made Dean of St. Patrick’s in 1713, and quickly gained a reputation for his notably long sermons. He is buried in the western end of the nave, alongside his great love, Esther Johnson.

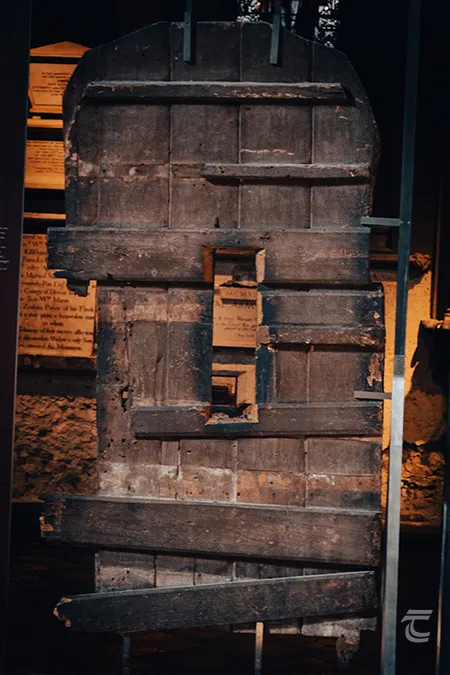

One of the more intriguing features is the so-called ‘Door of Reconciliation’, and according to a famous story, it is the origin of the phrase ‘to chance your arm’. Towards the end of the 15th century, rivalry between the powerful Butlers of Ormonde and the FitzGeralds of Kildare broke into a violent feud. A skirmish was fought on the outskirts of Dublin. The Butlers retreated and took refuge in the Chapter House of Saint Patrick’s Cathedral. The FitzGeralds followed them into the Cathedral and demanded that they come out and make peace. The Butlers, with justifiable caution at the time, were afraid that if they did so they would be massacred, and so they refused. As a gesture of good faith Gerald FitzGerald ordered that a hole be cut in the door. He then thrust his arm through the door and offered his hand in peace to those on the other side. By making himself so vulnerable, FitzGerald reassured the Butlers that FitzGerald truly wanted an end to the fighting so they opened the door. Unusually for Medieval Ireland it ended peacefully, with a cessation of hostilities.

Perhaps the most elaborate monument is the 17th century tomb of Richard Boyle, Earl of Cork and his wife. This exceptionally tall monument has life-size effigies of the first earl of Cork and his wife Katherine Fenton, as well as eleven of their children and Katherine’s mother, father and grandfather. Close by is the slightly more modest, but still rather extravagant, tomb of Archbishop Thomas Jones who died in 1619. Even in death it’s difficult to keep up with the Joneses!

Some of the more than 200 monuments of St Patrick’s Cathedral • Dublin

In 1783, King George III established the Most Illustrious Order of St Patrick, an honours system for Irish peers to bolster support for the Crown in the Irish parliament. The Order was relatively short-lived, and became effectively defunct in 1922 on the creation of the Irish Free State. However, you can still see the many banners of the Knights of St Patrick prominently displayed, hanging proudly over the choir stalls.

Following the Irish Church Act of 1869 and the disestablishment of the Church of Ireland, Christ Church was appointed the diocesan cathedral, with St Patrick’s becoming the national cathedral of the country. In 1949, it was the location for the state funeral of Ireland’s first president, Douglas Hyde, and again a quarter of a century later for President Erskine Childers. Monuments to both men were commissioned, and can be seen in the south aisle of the cathedral.

With all its gothic splendour and wealth of monuments, St Patrick’s Cathedral is a wonderful place to while away an hour or two on your next visit to Dublin City!

Left: the elaborate Boyle tomb • Middle upper: the Lady Chapel • Middle lower: the choir of St Patrick’s Cathedral and the banners of the Knights of St Patrick • Right: the ‘Door of Reconciliation’

Top: the elaborate Boyle tomb • Second: the Lady Chapel • Third: the ‘Door of Reconciliation’ • Bottom: the choir of St Patrick’s Cathedral and the banners of the Knights of St Patrick

Explore more sites around Dublin