Monasterboice High Crosses and Round Tower

The Monasterboice High Crosses stand in a small graveyard, north of the Boyne in County Louth. They are undoubtedly some of Ireland’s (and the world’s) greatest treasures. It is no exaggeration to say that they are perhaps the finest artistic and spiritual expressions of the early medieval period carved in stone. These three high crosses were crafted around a thousand years ago; one is rather plain, another the tallest in the land, while the last is a true wonder. Remarkably well-preserved, the Monasterboice High Crosses have withstood over ten centuries of Irish weather. Their beauty, scale and antiquity make it a wonder.

The name ‘Monasterboice’ derives from the Latin Monasterium Boecii, meaning the monastery of Boecius. Boecius is the Latin form of Buithe, an Irish saint born during the 6th century, who is thought to have died in AD 521. Over time the monastery flourished and grew in both size and prominence, with a number of references in the Irish Annals from the 8th century until the 12th century. This apparent decline may coincide with the large reforms of the Irish church during the 12th century. This was a time when new foundations with continental links, such as nearby Mellifont, began to overshadow and supersede some of the older establishments. Indeed, Monasterboice was eventually reduced to the status of a parish church. The settlement that once flourished in the shadow of the monastery became dispersed, and a new settlement was established a little further away.

Despite the decline in status, Monasterboice remained an important place for pilgrimage up until the 17th century, when the site was described as being in ruins. However the graveyard has continued in use right up until the present day. With over 40 generations of the local community sharing their resting place with ancient saints.

You can read more about the key features of Monasterboice below. If you’d like to delve deeper into the story of the crosses and how they were constructed, Early Irish Sculpture and the Art of the High Crosses by Professor Roger Stalley is a wonderful publication.

For practical information about visiting this site Click Here

The Monasterboice High Crosses stand in a small graveyard, north of the Boyne in County Louth. They are undoubtedly some of Ireland’s (and the world’s) greatest treasures. It is no exaggeration to say that they are perhaps the finest artistic and spiritual expressions of the early medieval period carved in stone. These three high crosses were crafted around a thousand years ago; one is rather plain, another the tallest in the land, while the last is a true wonder. Remarkably well-preserved, the Monasterboice High Crosses have withstood over ten centuries of Irish weather. Their beauty, scale and antiquity make it a wonder.

The name ‘Monasterboice’ derives from the Latin Monasterium Boecii, meaning the monastery of Boecius. Boecius is the Latin form of Buithe, an Irish

saint born during the 6th century, who is thought to have died in AD 521. Over time the monastery flourished and grew in both size and prominence, with a number of references in the Irish Annals from the 8th century until the 12th century. This apparent decline may coincide with the large reforms of the Irish church during the 12th century. This was a time when new foundations with continental links, such as nearby Mellifont, began to overshadow and supersede some of the older establishments. Indeed, Monasterboice was eventually reduced to the status of a parish church. The settlement that once flourished in the shadow of the monastery became dispersed, and a new settlement was established a little further away.

Despite the decline in status, Monasterboice remained an important place for pilgrimage up until the 17th century, when the site was described as being in ruins. However the graveyard has continued in use right up until the present day. With over 40 generations of the local community sharing their resting place with ancient saints.

You can read more about the key features of Monasterboice below. If you’d like to delve deeper into the story of the crosses and how they were constructed, Early Irish Sculpture and the Art of the High Crosses by Professor Roger Stalley is a wonderful publication.

For practical information about visiting this site Click Here

The head of Muiredach’s Cross, Monasterboice • Louth

Monasterboice Monastic Site

There are a number of features at Monasterboice that give an indication of the prestige and significance of the monastery, and research has demonstrated that the site that we see today is only the innermost core of what was once an expansive monastic foundation. Geophysical surveys carried out in 2008 provided further details to features that had been spotted from aerial photography. These features spread far beyond the bounds of the churchyard that we see today, lying underneath the agricultural fields that surround the site. They consist of a complex of enormous enclosures, with the present churchyard occupying the innermost enclosure. According to the written sources, an early Irish monastery was divided by enclosures of increasing holiness – the sanctus on the outside, the sanctior in the middle and the sanctissimus at the centre.

The survey, along with the aerial photography and a number of other discoveries in the course of agricultural work, also identified that there was a large settlement in the surrounding fields. There have been discoveries of souterrains (underground, stone-lined passageways that were used as a cold storage or for refuge), along with traces of structures. This is where the lay population who served the monastery lived. Evidence from excavations at comparable sites like Clonmacnoise, shows that as well as being spiritual centres, Ireland’s early monasteries were served by farming, craftwork, trade and industry. They were the biggest population centres prior to the Vikings, who established secular ‘towns’ at places like Waterford, Dublin, Cork and Limerick.

However, today much of that once bustling settlement is completely invisible to the visitor to Monasterboice. All that remains tangible is the very heart of the monastery, with its round tower and high crosses. The section below highlights some of the main features of Monasterboice, with a particular focus on the remarkable high crosses.

The Churches of Monasterboice

You can find the ruins of two churches at Monasterboice. The Southern Church is the larger, and it served as a parish church from the later medieval period until the site fell into ruin in the 17th century. It was possibly first built as early as the 11th century, as a simple rectangular church with a lintelled western doorway. Later, it was developed into a nave and chancel church, though today the chancel is largely lost. Fragments of a stone shrine were incorporated as quoins in the western wall. A bullaun stone is set at the southern end of the church. This stone with a circular hollow may have originated as the upper part of a rotary quern stone. Or it may have been used as a rudimentary holy water font during the early days of the monastery, or perhaps as a large version of a pestle-and- mortar, maybe to grind herbs, ore for metallurgy, or pigments for manuscript illustration.

The Northern Church of Monasterboice is smaller, though it has the remains of two doorways and four windows. According to the archaeologist Con Manning, this church may have replaced an early shrine church that was dedicated to St Buíthe. It is said to have housed a relic of the head of the saint, which was stolen in the 16th century.

The interior of the South Church

Inside the ruin of the North Church

The Churches of Monasterboice

The interior of the South Church

You can find the ruins of two churches at Monasterboice. The Southern Church is the larger, and it served as a parish church from the later medieval period until the site fell into ruin in the 17th century. It was possibly first built as early as the 11th century, as a simple rectangular church with a lintelled western doorway. Later, it was developed into a nave and chancel church, though today the chancel is largely lost. Fragments of a stone shrine were incorporated as quoins in the western wall. A bullaun stone is set at the southern end of the church. This stone with a circular hollow may have originated as the upper part of a rotary quern stone. Or it may have been used as a rudimentary holy water font during the early days of the monastery, or perhaps as a large version of a pestle-and- mortar, maybe to grind herbs, ore for metallurgy, or pigments for manuscript illustration.

Inside the ruin of the North Church

The Northern Church of Monasterboice is smaller, though it has the remains of two doorways and four windows. According to the archaeologist Con Manning, this church may have replaced an early shrine church that was dedicated to St Buíthe. It is said to have housed a relic of the head of the saint, which was stolen in the 16th century.

Monasterboice Round Tower

Round Tower • Monasterboice

Though its conical cap does not survive, Monasterboice Round Tower is one of our finest examples. It stands approximately 30 metres (98 ft) tall. The iconic Irish round towers are thought to have been primarily constructed as bell towers as they are known as ‘cloigh teach’ in Irish, which translates as ‘bell house’. They would have been visible for miles around, and as such would have acted like a signpost to pilgrims on the route to Monasterboice. The tower is likely to date to the 11th century. It has a sandstone doorway that faces eastwards towards the churches, and one of the windows in particular is notable for being constructed of well-cut stone.

As well as serving as a belfry, the tower was also a place that held some of the most precious objects and manuscripts of the monastery. However, this met with disaster at Monasterboice at the end of the 11th century. As according to the Annals of the Four Masters, in 1097:

‘The cloictheach of Mainistir-Buithe, with its books and many treasures, were burned…’

Monasterboice Sun Dial

The head of the Sun Dial • Monasterboice

Monasterboice also has a fine example of a sun dial. These are relatively rare in Ireland (probably due to the weather!), and tend to be found in association with high status monasteries such as Nendrum, County Down, and Kilmalkedar, County Kerry. The monastic day was structured around the hours for work, rest and worship, so an indication of the time would have been important. Though weathered, you can see three incised lines radiating from the hole at the centre of the head. Each of these lines terminates in three prongs indicating the hours of terce (the third hour – 9am), sext (the sixth hour – noon) and none (the ninth hour – 3pm).

Some other architectural fragments are located around the foot of the sun dial, giving a faint impression of the splendour of this monastery in the past. However, the clearest indication of this comes from the remarkable high crosses.

The head of the Sun Dial • Monasterboice

The Monasterboice High Crosses

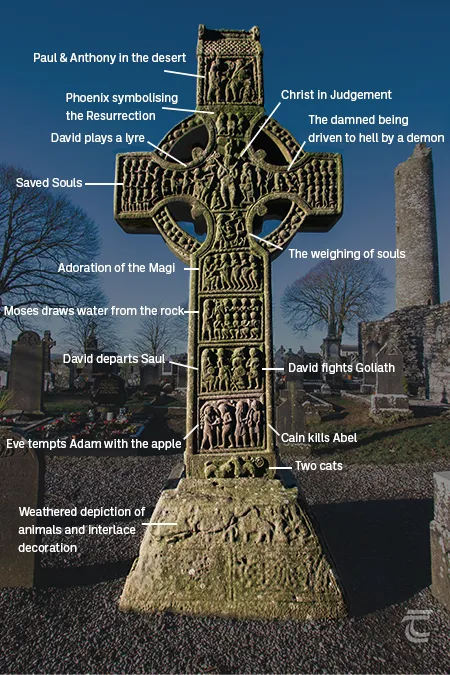

Muiredach’s Cross (also known as the South Cross)

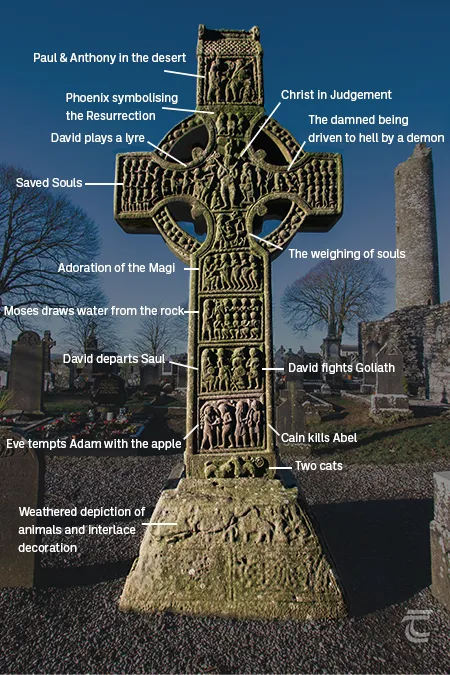

The East Face of Muiredach’s Cross.

Tap the image to see a description of the panels

Muiredach’s Cross, also known as The South Cross, is arguably the finest example of a high cross in Ireland. It is likely to date to the early-10th century, as it is very similar to the Cross of the Scriptures (also known as the West Cross) at Clonmacnoise, which was dated by an inscription to AD c.904–916. Indeed, so similar are the crosses in terms of artistic style, that Professor Roger Stalley believes that they were carved by the same master artisan. Who he refers to as ‘The Muiredach Master’ in his publication Early Irish Sculpture and the Art of the High Cross, which he discussed on this episode of Amplify Archaeology Podcast.

The East Face of Muiredach’s Cross.

Hover over the image to see a description of the panels

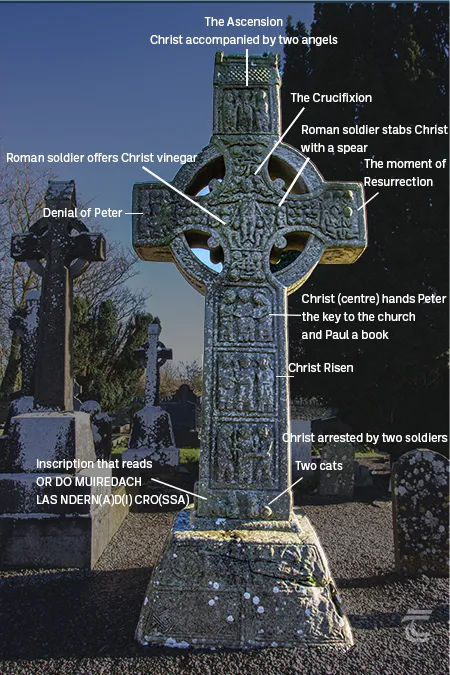

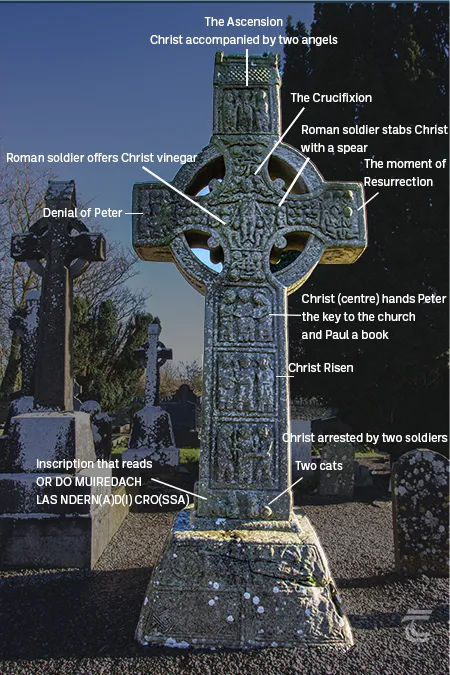

The West Face of Muiredach’s Cross.

Hover over the image to see a description of the panels

The West Face of Muiredach’s Cross.

Tap the image to see a description of the panels

Like the Clonmacnoise example, the South Cross at Monasterboice also bears an inscription, asking for ‘a Prayer for Muiredach’. It seems likely that this refers to Muiredach who died in AD 924. He was the abbot of Monasterboice, and the vice-abbot of Armagh. He was also the chief steward of the powerful Southern Uí Néill dynasty, making him an incredibly important and influential figure in both religious and secular Ireland.

The cross is simply one of the most important and visually stunning examples of early medieval sculpture in the world. It bears depictions from the New and Old Testaments, and charmingly, a pair of cats play at the base of the shaft.

The Tall Cross (also known as The West Cross)

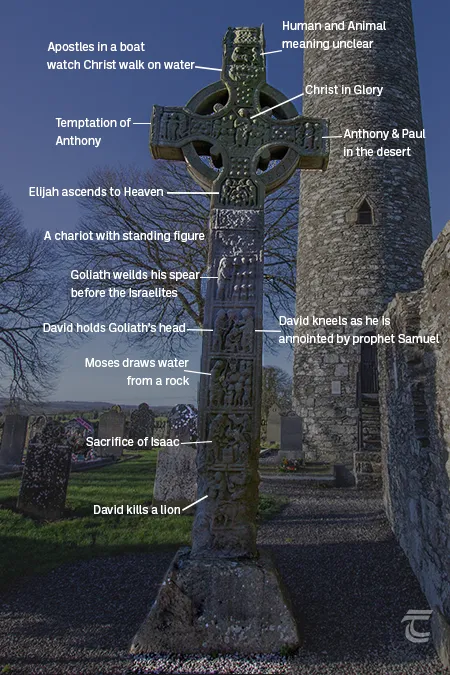

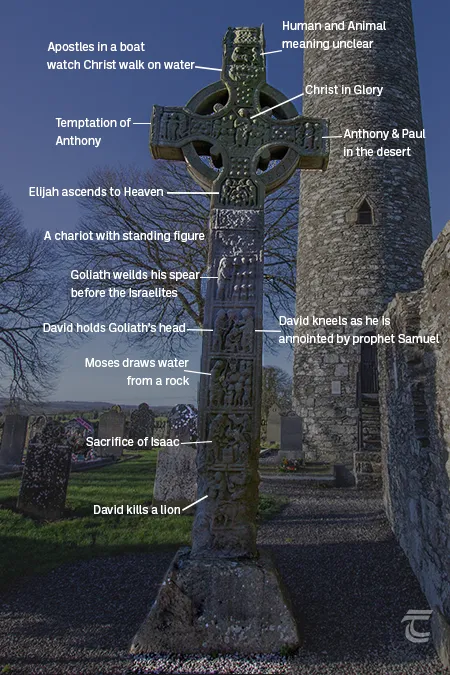

The East Face of the Tall Cross.

Hover over the image to see a description of the panels

The East Face of the Tall Cross.

Tap the image to see a description of the panels

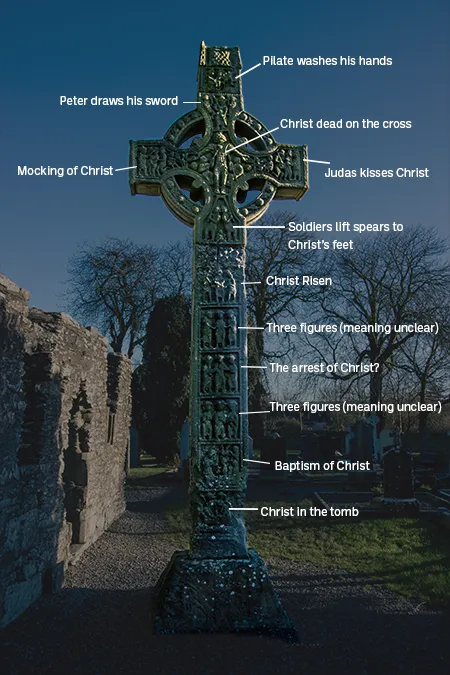

The West Face of the Tall Cross.

Hover over the image to see a description of the panels

The West Face of the Tall Cross.

Tap the image to see a description of the panels

The Tall Cross (or West Cross) is the tallest high cross in Ireland, standing at an impressive 6.5 metres (21 ft) tall. Thanks to its size, it also has the largest number of figure sculpture panels of any high cross. Like the South Cross these panels are beautifully carved with depictions representing biblical stories from both the Old and New Testaments.

The North Cross of Monasterboice

The East Face of the North Cross.

The West Face of the North Cross.

The North Cross is very different to the other two. It is much plainer, with little decoration. This is more typical of the slightly later high crosses of the 11th century. It is made up of three pieces today – the head with the top of the cross shaft, the lower part of the cross shaft, and a modern block set in between to connect them. The head of the cross on the eastern face is decorated with scrollwork set within a circular boss. While the western face has a depiction of the crucifixion, though far less elaborate than those on Muiredach’s Cross and the Tall Cross. This shows Christ in the centre, with two small Roman soldiers on either side of him, they appear to be using spears or lances to pierce his side. You can see this cross at the northern end of the site in the same small enclosure as the sundial, surrounded by railings. You can also see a cross slab in this enclosure, it bears the inscription OR DO RUARCAN (a prayer for Ruarcan).

Fragments from at least two other smaller crosses have been found at Monasterboice. Suggesting that the site had a remarkable five high crosses at one point. These fragments are on display in the Louth County Museum in Dundalk.

The West Face of the North Cross.

The graveyard of Monasterboice has been in use for centuries. Today there are around 400 headstones, with the earliest of the headstones dating to 1769. It is well worth viewing some of the historic headstones, as they provide an insight into life in the area through the ages. For example, some of the occupations indicated on the stones include, two doctors, a member of the Royal Irish Constabulary, a piper, a sea captain, a yarn merchant, a farmer, and three parish priests. Though do bear in mind that this is still a place of burial for the local community, so please respect the privacy of anyone visiting a grave.

In 1874 some members of the local community raised funds to carry out works. They constructed a boundary wall around the graveyard, and they added steps, timber floors and a viewing platform within the round tower. When the site came into state care, the Office of Public Works carried out conservation of the tower and removed the timber viewing platform though they left the steps and floors in place. The local community remain active custodians of the graveyard, and occasionally offer guided tours.

Upper left: the historic graveyard of Monasterboice • Lower left: the cats on Muiredach’s Cross • Right: the shaft of the eastern face of Muiredach’s Cross

Top: the historic graveyard of Monasterboice • Middle: the shaft of the eastern face of Muiredach’s Cross • Bottom: the cats on Muiredach’s Cross