Jerpoint Abbey

Jerpoint Abbey is located in the south of County Kilkenny, alongside the Little Arrigal River and contains a true wealth of wonderful medieval sculpture. The abbey is believed to have been founded by a donation by the King of Ossory Domnall Mac Gilla Pátraic in c. 1160, and was perhaps originally a Benedictine foundation but it was taken over by the Cistercian order by the late 12th century as a ‘daughter house’ to the abbey at Baltinglass. The abbey was well located, being close to the medieval settlement at Newtown Jerpoint with its important crossing point over the River Nore. By 1228, there were 36 monks and 50 lay brothers, with landholdings of approximately 20,000 acres of land. As well as the core monastic buildings, there were once fishponds, workshops, mills and farmsteads, as well as a brewery, infirmaries, gardens, orchards and guest quarters.

The abbey is laid out in the traditional Cistercian way, with a cruciform church with cloisters to the south. The abbey was adapted and changed throughout its history, particularly in the 15th century, when a papal indulgence was granted to raise funds for the renovation and repair of many of the buildings.

The Cistercians first came to Ireland in c. 1142, and established their first foundation at Mellifont in County Louth. By this time, the Cistercians were one of the most powerful religious orders in Europe. The life of a Cistercian monk was strictly apportioned between religious study and manual labour, with all tasks scheduled to fit around regular communal prayers. Every night the monks arose for Matins at about 2 am, then Lauds at 5 am, Prime at 6 am, Terce at 9 am, Sext at noon, Nones at 3 pm, Vespers around 5 pm and finally Compline at 6 pm. It was a life of almost unvarying routine and absolute discipline. Monks performed their tasks in silence, their meals were plain and largely vegetarian and their habits were made of coarse, undyed wool. A Cistercian monk in England, Ailred of Rievaulx, described the daily experience, ‘Our food is scanty, our garments rough; our drink is from the stream and our sleep often upon our book. Under our tired limbs there is but a hard mat; when sleep is sweetest, we must rise at bell’s bidding. Self-will has no place; there is no moment for idleness or dissipation.’

The Dissolution of the Monasteries saw the end of Jerpoint in 1540. The last abbot, Oliver Grace, along with the remaining five monks, left without their possessions. The abbey and its holdings were leased to the powerful Butlers of Ormond.

For practical information about visiting this site Click Here

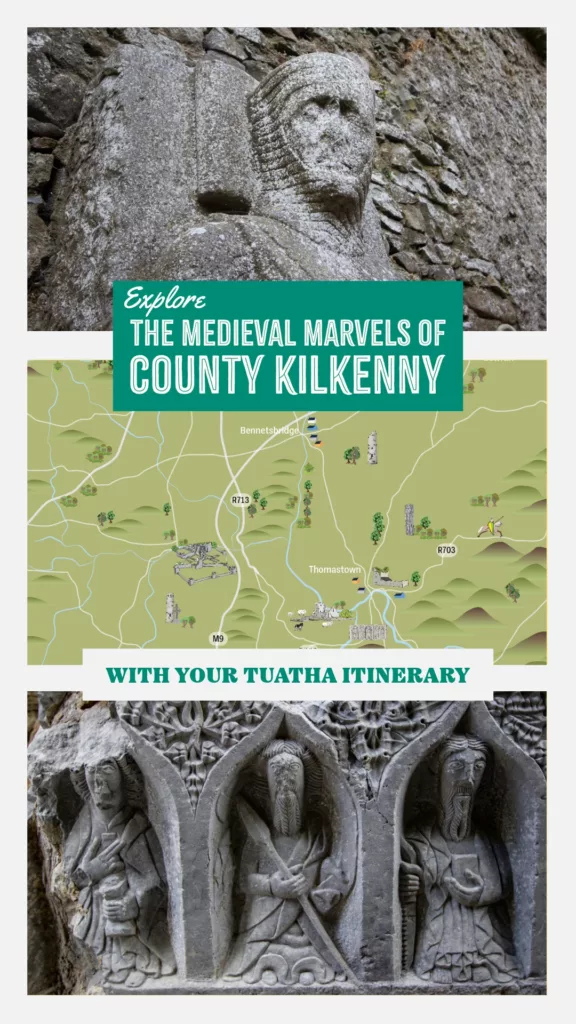

The ‘weepers’ of a stone tomb in Jerpoint Abbey • Kilkenny

Jerpoint’s Medieval Sculpture

A dragon on one of the columns in the cloister • Kilkenny

This austere life contrasts quite sharply with some of the elaborate, charming and sometimes humorous sculptures and depictions around the abbey. Inside the church is a wealth of medieval tombs, some with ‘weepers’ (i.e. sculptures of the apostles and saints surrounding the base of the tomb). Many of these were created by the workshop of medieval master-sculptor Rory O’Tunney, who was based nearby at Callan. The saints are recognisable as many hold a symbol to identify them, like St Peter who is often depicted holding the keys of heaven. Others hold symbols of their martyrdom; for example, St Thomas holds a lance, St Simon a saw, St Andrew an X-shaped cross, St Bartholomew his skin (he was flayed alive), and St Paul a sword.

A number of other fascinating tomb effigies can also be seen, the earliest of which is that of Abbot O’Dulany who died in 1202. Perhaps most intriguing is the effigy of two Norman knights known locally as ‘The Brethren’, depicted in their armour side by side. It is a highly unusual stone, as there are few incised graveslabs that depict knights known from Ireland (or elsewhere). The depiction is certainly intimate. The knights are positioned in a manner you would more commonly see a married couple, with arms touching and the knight on the left facing the knight on the right. At this time, no women had been granted the title of knight in Ireland, though some orders anointed female warriors, known as ‘dames’. So it may be a depiction of a married couple of a man and woman, or perhaps a male couple (though such a depiction would be highly unusual at this time). Or perhaps it could be two male relatives, a father and son, or brothers. Local folklore suggests that the slab may represent two of the sons of William Marshal. Or possibly it could just be two very close friends and blood brothers? We will likely never know for sure, but the slab is an intimate and touching depiction of partnership and love, whether platonic or otherwise.

The cloister contains an almost unparalleled wealth of sculpture, where saints, religious figures, courtly ladies, knights and fantastical beasts like dragons and manticores can all be seen, some carved with a sense of humour that one might not expect in an austere Cistercian abbey. Especially as the influential Cistercian leader St. Bernard of Clairvaux had issued a strong condemnation of such carvings during his feud with the Benedictine abbey of Cluny:

A dragon on one of the columns in the cloister • Kilkenny

‘…But in cloisters, where the brothers are reading, what is the point of this ridiculous monstrosity, this shapely misshapenness, this misshapen shapeliness? What is the point of those unclean apes, fierce lions, monstrous centaurs, halfmen, striped tigers, fighting soldiers and hunters blowing their horns?… In short, so many and so marvellous are the various shapes surrounding us that it is more pleasant to read the marble than the books, and to spend the whole day marvelling over these things rather than meditating on the law of God. Good Lord! If we aren’t embarrassed by the silliness of it all, shouldn’t we at least be disgusted by the expense?’

It may not be to Bernard’s austere taste, but I always find exploring Jerpoint to be a rewarding day out. Each time I revisit I notice some other great sculpture or detail I had overlooked before. Jerpoint is under the auspices of the OPW. It has an informative visitor centre and there are guided tours available.

Upper left: an effigy of two knights, known as ‘The Brethren’ • Lower left: exterior view of Jerpoint Abbey • Right: sculptures on the cloister’s columns, including one depicting an abbot, and another of a knight

Top: an effigy of two knights, known as ‘The Brethren’ • Middle: sculptures on the cloister’s columns, including one depicting an abbot, and another of a knight • Bottom: exterior view of Jerpoint Abbey