Glendalough Monastery

Glendalough Monastery is a perfect blend of scenery and story. As such, it has become one of Ireland’s most iconic and recognisable heritage sites and a star of many tourism posters, postcards and tea towels. But beyond the serenity, Glendalough has a fascinating and complex story that spans centuries. The name Glendalough comes from the Irish Gleann Dá Loch, meaning the ‘Valley of the Two Lakes’. The site is most famous for the monastery of Glendalough, that was founded by St Kevin some time in the later part of the 6th century. From its early origins, Glendalough became one of the most significant centres of Christianity.

St Kevin, or Cóemhghein, meaning ‘fair begotten’ or ‘gentle one’, is believed to have been a descendant of one of the ruling families in Leinster, the Dál Messin Corb. He died in around c.620, and as with many of our early saints, the stories of Kevin were written centuries after his death. The majority of the stories come from the 12th century Latin text Life of St Kevin, contained within the collection known as the Codex Salmanticensis. There are also a number of other hagiographical accounts of Kevin, and as with all such accounts from the period, they are replete with fantastical tales and miraculous events. One of the best known stories of Kevin, describes how he wished to worship God by living the harsh life of an ascetic hermit. On one occasion he prayed for so long while standing in the freezing waters of the Upper Lake at Glendalough, birds built nests in his outstretched hands and laid eggs.

For practical information about visiting this site Click Here.

Glendalough Monastery is a perfect blend of scenery and story. As such, it has become one of Ireland’s most iconic and recognisable heritage sites and a star of many tourism posters, postcards and tea towels. But beyond the serenity, Glendalough has a fascinating and complex story that spans centuries. The name Glendalough comes from the Irish Gleann Dá Loch, meaning the ‘Valley of the Two Lakes’. The site is most famous for the monastery of Glendalough, that was founded by St Kevin some time in the later part of the 6th century. From its early origins, Glendalough became one of the most significant centres of Christianity.

St Kevin, or Cóemhghein, meaning ‘fair begotten’ or ‘gentle one’, is believed to have been a descendant of one of the ruling families in Leinster, the Dál Messin Corb. He died in around c.620, and as with many of our early saints, the stories of Kevin were written centuries after his death. The majority of the stories come from the 12th century Latin text Life of St Kevin, contained within the collection known as the Codex Salmanticensis. There are also a number of other hagiographical accounts of Kevin, and as with all such accounts from the period, they are replete with fantastical tales and miraculous events. One of the best known stories of Kevin, describes how he wished to worship God by living the harsh life of an ascetic hermit. On one occasion he prayed for so long while standing in the freezing waters of the Upper Lake at Glendalough, birds built nests in his outstretched hands and laid eggs.

For practical information about visiting this site Click Here.

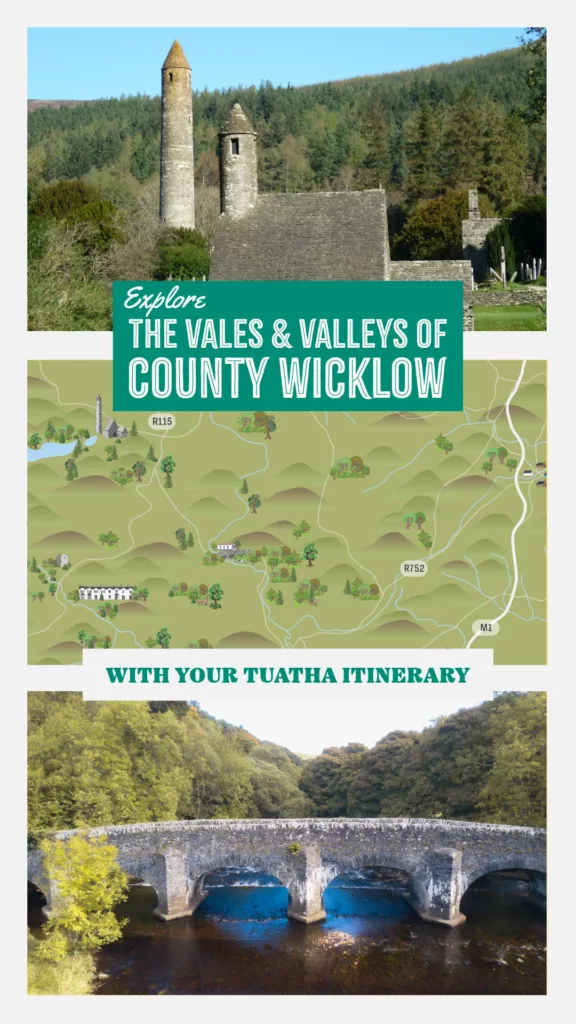

With a blend of stunning scenery and history, Glendalough is one of Ireland’s most iconic sites • Wicklow

If you’re a Tuatha Member make sure that you’re logged in, to discover the off the beaten track parts of Glendalough that most visitors miss.

The History of Glendalough Monastery

Although the place that Kevin chose to found his community at Glendalough appears wild and solitary, it is close to the Wicklow Gap, a major trading route through the hills. This gave the growing Christian community a good balance between monastic isolation and easy access to the pilgrims who increased the wealth and significance of the site. Recent excavations by UCD School of Archaeology, and some of the lesser known features around the complex, also point to Glendalough as a centre of industry and craft as well as spirituality, so trade links were essential. You can hear more about this in the very first episode of our Amplify Archaeology Podcast.

However, these same routes brought problems as well as pilgrims. Like most early Irish monasteries, Glendalough was raided a number of times in its history. It was attacked by both the Vikings and by Irish kingdoms. Great religious centres like Glendalough Monastery, were also politically powerful, and various Irish kings and rulers sought to either become benefactors of the monastery, or to diminish it in favour of their own.

The powerful King of Munster Muirchertach Ua Briain was one key patron. Many of the key buildings that we can see today – St Kevin’s Church, Reefert Church, The Round Tower, Cathedral and Trinity Church – may have all been built under his patronage. His mother, Derborgaill, died at Glendalough in 1098, and she may have been the patron of St Mary’s Church. The patronage of such a powerful dynasty meant that when the Synod of Ráth Breasail took place in 1111, Glendalough was appointed as a diocese, with Dublin under its authority. Though power always ebbed and flowed in medieval Ireland, and Glendalough would eventually be subsumed itself under a new diocese of Dublin.

One of the key figures at Glendalough was the famous Lorcán Ua Tuathail – known to us today as St Laurence O’Toole. He was a member of the Ua Tuathail family that long held a powerful role in the Wicklow Mountains. He was abbot of Glendalough from 1153, and became Bishop of Dublin and Glendalough in 1162. St Saviour’s Church outside the main complex dates to his time. After his death he was canonised, becoming the second saint of Glendalough after Kevin.

Most of the churches of Glendalough were in ruins by the 17th century, though it continued to be an important place for pilgrimage. There was a pattern day held on the feast of St Kevin on the 3rd June, where huge numbers of pilgrims would congregate. This occasionally got out of hand, with reports of drinking and faction fighting and it was described as a ‘riotous assembly’ in 1714 by the High Sheriff of Wicklow. The pattern day was eventually brought to an end in 1862 by the Archbishop of Dublin, Cardinal Cullen, who disliked the superstition and chaotic behaviour of the pilgrims.

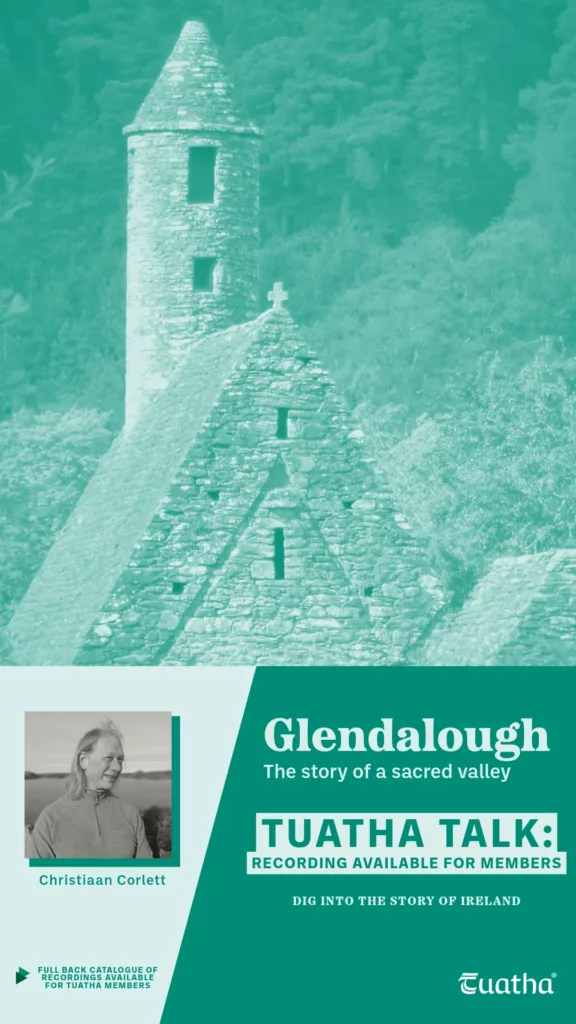

Our Tuatha Tour of Glendalough with archaeologist Christiaan Corlett

During the 18th and 19th century, Glendalough’s scenic beauty and atmospheric ruins attracted many antiquarians and culture seekers. These included William Wilde (father of Oscar Wilde), George Petrie, John O’Donovan of the Ordnance Survey, and the Dutch-Huguenot artist Gabriel Beranger, whose illustration of the Priest’s House was used to guide the restoration and reconstruction. The Office of Public Works began the restoration and conservation works at Glendalough Monastery from 1875. St Saviour’s Church and the Priest’s House were substantially reconstructed, and they reconstructed the conical cap of the round tower. In a wonderful link with the past, the masons who carried out the work on the round tower used the same putlog holes for their scaffolding as those who first built the tower centuries earlier. Though sadly, they filled in the putlog holes when they finished their work, meaning they are not visible to us today.

For a deeper dive into the history of Glendalough, we recommend Christiaan Corlett’s beautifully illustrated publication Glendalough (though it can be difficult to find in print). It is also well worth seeking out the monograph Glendalough, City of God published by Four Courts Press, and the monumental Churches in the Irish Landscape AD 400-1100 by Tomás Ó Carragáin. UCD School of Archaeology also have a lot of information freely available on their excavations here. As do the local community, who have lots of information on their work on the excellent Our Wicklow Heritage website. The National Museum of Ireland currently has an exhibition dedicated to Glendalough and featuring some of the artefacts discovered during the recent excavations. You can find more information on that here.

The following section has an outline of the key features of Glendalough Monastery in the order that you might encounter them as a visitor. The main cluster of historic buildings are around the Lower Lake, while the Upper Lake has some key sites too. However, if you have the time and inclination to explore, there are many wonderful satellite features that are often overlooked by visitors, as well as spectacular walking trails (if you are a Tuatha Member, make sure you are logged in to see this extra content). One visit to Glendalough is never enough!

Glendalough Lower Lake

Glendalough Visitor Centre

The Market Cross • Glendalough Monastery Visitor Centre

The original churches and monastic buildings from the earliest phases at Glendalough were constructed of timber so nothing survives of those above the ground. Most of the structures you see now at Glendalough date to between the 11th to the 12th centuries. The most famous here are clustered near to the Lower Lake, only a very short stroll from the car park. The Glendalough Visitor Centre tells the story of the site, with exhibitions and an audio visual. The Visitor Centre also houses some of the decorated cross slabs, and the Market Cross. The Market Cross dates to the 12th century. It is highly decorated with interlace, and a sculpture of Christ. Below Christ, there is a figure in priestly robes, possibly representing St Kevin.

Leaving the Visitor Centre, turn right when you exit and follow along the path behind the hotel while following the signs to the monastic city. This should bring you to the original gateway into the site.

The Market Cross • Glendalough Monastery Visitor Centre

The Gateway

The Gateway • Glendalough Monastery

The Gateway to Glendalough dates to the early 12th century, and it is fascinating to think of how many visitors have passed under its arches over the centuries. This is the only surviving example of an early monastic gatehouse in Ireland. Glendalough’s gatehouse differentiates itself from the gates into a secular walled town (like Dublin), by some church-like features. Such as the projecting antae, that are unique to early stone churches. More obviously, just inside the gate you can see a very large stone incised with a cross. This may have marked the point of sanctuary, once within the sacred boundary you may have gained immunity from prosecution or violence.

The Gateway • Glendalough Monastery

The Historic Graveyard

The historic graveyard • Glendalough

The historic graveyard that surrounds many of the monastic features is itself well worth a closer look. It has an array of monuments and headstones all set within a large quadrangular enclosure between the Glendasan and Glenealo rivers. A 2016 survey by local community volunteers, led by Glendalough Heritage Forum and supported by UCD School of Archaeology and John Tierney of Historic Graves, and funded by the Heritage Council, recorded 1,400 grave monuments. The monuments ranged from uninscribed stone markers, to more ornate headstones, with inscriptions ranging in date from 1731 to the present day. The survey can be accessed here. There can be few final resting places as beautiful as Glendalough.

The Round Tower

The Round Tower • Glendalough Monastery

Standing proudly in the valley, the round tower is one of the iconic images of Glendalough. It was possibly built around 1100, when there was a renewed investment and development of stone building at Glendalough, under the auspices of Muirchertach Ua Briain. The Glendalough Round Tower stands over 30 metres (98 ft) tall and around 5m in diameter at the base. The doorway is set 3m off the ground and faces towards the cathedral. It has windows facing the cardinal points of north, east, south and west. The conical cap forming the roof of the round tower was reconstructed in the 1870s by a team including William Wilde, father of the famous Oscar Wilde. William was a noted antiquarian and was responsible for much of the renovation and restoration of Glendalough as well as a number of other ancient Irish sites.

The Round Tower • Glendalough Monastery

The Cathedral

The chancel arch of the Cathedral • Glendalough Monastery

The Cathedral is the largest stone building of Glendalough monastery. It consists of a nave and chancel, with a sacristy attached to the southern side of the chancel. The architecture of the building shows that it was constructed in several phases from the 10th to the 13th century. The earliest part of the Cathedral appears to be the nave, which was once a simple rectangular church with a doorway to the west and windows along the southern wall. The nave has antae, which are projections of the side walls, a reasonably typical feature of the earlier stone churches in Ireland. Archaeologist Con Manning noted that the lower courses of the nave walls of the Cathedral are dramatically different to the rest of the stonework. They consist of large stone blocks, and they may have been quarried from an earlier stone church that was demolished or recycled into the expanded nave, presumably in around the late 11th or early 12th century. The chancel was added in the second half of the 12th century, with a chancel arch decorated with the chevrons and zigzags that are typical of Hiberno-Romanesque architecture. Finally in the 15th century, a parapet was added, but only traces of this remain in the south wall of the chancel.

St Kevin’s Cross and the Priest’s House

The remains of the Priest’s House • Glendalough Monastery

St Kevin’s Cross is a finely carved plain ringed-cross standing just south of the Cathedral. It stands some 3.5m tall, and is carved from a single block of granite. Tradition claims that you will have good fortune if you can join your arms when you hug the cross.

The small building known as the ‘Priest’s House’ takes its name from its role as a burial place for Catholic priests in the late-18th century. The building is rather difficult to decipher, as it has been subject to large-scale reconstruction in the late 19th century. It may once have been a small shrine chapel that held relics associated with St Kevin. Fragments of fine Hiberno-Romanesque sculpture can be seen in the building, similar to that at St Saviour’s Church, and the same master-artisans may have been involved. A carved stone thought to depict St Kevin with a kneeling bishop and abbot, was found close to the Priest’s House. The stone has been reused as a lintel into the building as part of the 19th century reconstruction. You can see a plaster cast of this in the National Museum of Ireland.

The remains of the Priest’s House • Glendalough Monastery

St Kevin’s Church

St Kevin’s Church • Glendalough Monastery

St. Kevins Church is one of the most recognisable features of Glendalough. The church is often referred to as St. Kevins Kitchen, as the belfry on top of the roof has the appearance of a chimney on an old fashioned stove. This is one of a very small group of stone vaulted and roofed churches in Ireland dating to this period. It likely dates to around 1100, though at least two phases of construction can be seen. The early phase consisted of a rectangular church with a stone roof with its small circular belfry. Later, a chancel and an interconnecting structure were added on. The chancel does not survive, but the adjoining structure does, giving the overall building an asymetrical appearance. You can still see the pitch of stone roof of the chancel in the triangular scar of the eastern face of the church. It was illustrated in 1779 by Angelo Maria Bigari, and you can see the illustration in the collection of the National Library of Ireland here. The small adjoining structure has been interpreted as a sacristy, though it may have been an anchorite cell.

Looking up you can see the barrel vault of the roof. It appears that there was once a small room above the church, though its wooden floor has long since disappeared. Another small room is above this, and may have stored valuables and manuscripts. The belfry has windows facing the cardinal points like the Round Tower, and a bronze bell found nearby may have been the original bell that once hung here. You can see the bell on display in the National Museum of Ireland.

The interior of the church is visible through the gated doorway, where a number of cross slabs, a cross head, millstones and other architectural features are kept for safekeeping and to prevent them from weathering. Although the church looks quite dark and damp inside today, when it was in use it was likely to have been plastered and whitewashed and then painted in vividly coloured murals that depicted key scenes from the bible or the life of St. Kevin. When illuminated with beeswax and tallow candles the church would have been an atmospheric and engaging place to pray.

St Kevin’s Church and the Round Tower • Glendalough Monastery

St Ciarán’s Church

St Ciarán’s Church • Glendalough Monastery

St Ciarán’s Church only survives as a low foundation, that maintains its shape as a small nave and chancel church. St Ciarán was one of the major saints of early Ireland, and particularly associated with his great foundation at Clonmacnoise. In the Life of Saint Kevin, the Wicklow saint travels to Clonmacnoise to meet his contemporary, only to find that Ciarán had died just three days before his arrival. Kevin asked for time alone to pray over the body, and according to the story Ciarán’s spirit briefly returned so the two saints could have a conversation. Another story relates how Ciarán presented Kevin with a bell. Though geographically quite distant, Clonmacnoise and Glendalough were closely connected, and this church is further evidence of that mutual support.

The Deerstone

The Deerstone • Glendalough Monastery

This stone with a hollow depression is located just after the bridge to the south of the main monastic complex, and adjacent to the path known as the Green Road. It appears to be a bullaun stone. Bullauns are often found in association with early monastic sites, and Glendalough has a particularly sizeable concentration of them (see Seven Fonts below). The Deerstone takes its name from a legend that tells of when St Kevin needed milk for an orphaned baby, a doe appeared here waiting to be milked. It was one of the key locations of the later pattern day pilgrimages. A 19th century account detailed here, describes how the waters collected in the hollow are curative, though to be effective, it should ‘be visited fasting before sunrise on a Sunday, Tuesday and Thursday in the same week and on each occasion a part of the ceremony is to crawl round it seven times on the bare knees with the necessary prayers’. Sadly this stone was badly damaged in the summer of 2023, when somebody lit a large fire in hole. The heat led to the stone becoming cracked and discoloured.

The Deerstone • Glendalough Monastery

St Mary’s Church

St Mary’s Church at sunrise • Glendalough Monastery

St Mary’s Church is visible in the field directly across from the graveyard opposite the cathedral and round tower. This church is thought to have been a nunnery. According to the Irish Lives of St Kevin, the saint found two women who had been murdered nearby. He resurrected them, and in his honour they became nuns, and established this church. In truth the church is from centuries after St Kevin’s life. It may have been founded for Derbogaill, mother of the King of Munster Muirchertach Ua Briain. She died at Glendalough in 1098, and had likely became a nun for the last years of her life.

Like many of Glendalough’s churches, St Mary’s has a number of visible phases of construction. It began as a simple rectangular stone church, with a chancel added at the eastern end in the later 12th century. As you pass under the doorway, look up. You will see the underside of the lintel is decorated with a saltire cross.

Glendalough Upper Lake

The Caher or Stone Fort

The Round Tower • Rock of Cashel

Two enclosures are recorded near the eastern shore of the Upper Lake at Glendalough. Of these, only one is still visible above the surface of the ground today with the other destroyed in the late 19th or early 20th century. The surviving enclosure is known as ‘The Caher’ or ‘The Stone Fort’. Today it appears as a circular drystone wall. The wall is a mid-20th century reconstruction. Surveys and excavation by UCD School of Archaeology identified that the reconstructed wall partially stands on a low earthen bank, that is accompanied by a ditch. They excavated sections of the ditch, and found material in the lower fills that was dated to AD 428–593. This very early date is particularly interesting, as it slightly predates St Kevin’s arrival in the valley, suggesting he didn’t find it as a wild solitary place. But a living and working landscape. The excavations also found evidence for metalworking, in the form of substantial lumps of smithing hearth base present along with charcoal in the lower fills. They also found animal bone, indicating that people were processing or consuming meat either in the enclosure or in its immediate vicinity. All of this is typical material associated with secular ringforts, and as the excavators suggest, the original use of this monument was not solely a spiritual one but was connected to everyday life.

The Round Tower • Rock of Cashel

Stone Crosses

Penitential Station • Glendalough Monastery

There are a line of stone crosses set on cairns (or leachta) situated close to the fort. The crosses themselves may be early medieval in date, though the cairns may have been established as penitential stations as part of the pilgrimage landscape. With the pilgrim completing ’rounds’ by visiting each of the stations and completing prescribed actions and prayers at each stop (similar to the Turas Glencolmcille). Though UCD excavations found evidence that at least one of the cairns was reconstructed in the 20th century, they were recorded on an 18th century map. This indicates the tradition extends centuries into the past, perhaps even to the time of the medieval monastery, when its status as an important centre of pilgrimage had been established.

Reefert Church

Autumn colours at Reefert Church • Glendalough Monastery

Situated in a wooded hollow near to the Upper Lake, Reefert Church is one of the most atmospheric features of Glendalough and it is particularly beautiful when the autumn colour sets in. The name Reefert derives from the Irish ‘Ríogh Fheart’ which translates as ‘the Burial Place of Kings’. It is traditionally believed to be the resting place of the powerful O’Toole family and other leading dynasties of the region. A small nave and chancel church was built here in around AD 1100, though it may not have been the original church on the site. The doorway appears to be made from reused from an older church. A number of early crosses can be seen in the graveyard, including a decorated stone cross. Other decorated stone graveslabs and a stone cross can be seen in the Visitor Centre, and in the vault of St Kevin’s Church where they are placed to keep them from weathering.

Autumn colours at Reefert Church • Glendalough Monastery

St Kevin’s Bed and Temple-na-Skellig

The Upper Lake • Glendalough

A cave in the rock face above the Upper Lake is known as St Kevin’s Bed, where, according to tradition, Kevin spent many days in prayerful isolation. The cave is thought to have been partially man-made sometime in the prehistoric period, perhaps as a Bronze Age tomb or the remnants of an early mine. In the past no pilgrimage to Glendalough was complete without a visit to this cave, and even into the 18th century expectant mothers would make the arduous climb into the cave to seek protection during their pregnancy and childbirth.

Temple-na-Skellig (meaning Church of the Rock) is located nearby. This church dates from the 12th century, and is likely to have been constructed on the site of an earlier wooden church. Archaeological excavations nearby revealed evidence of huts made from hazel wattle, suggesting that there could have been an early settlement here, perhaps the location for the earliest phase of the monastery. Unfortunately, there is currently no access to St Kevin’s Bed or Temple-na-Skellig.

Off the beaten track – the satellite churches and other features of Glendalough Monastery

If you’re a Tuatha Member make sure that you’re logged in, to discover sites off the beaten track of Glendalough that most visitors miss.

Left: St Kevin’s Church • Top Centre: UCD archaeological excavations underway at Glendalough • Bottom Centre: Romanesque decoration at St Saviour’s Church, the centre shows a boat that may be a depiction of the Brendan Voyage • Right: St Kevin’s Cross

1. St Kevin’s Church • 2. UCD archaeological excavations underway at Glendalough • 3. St Kevin’s Cross • 4. Romanesque decoration at St Saviour’s Church, the centre shows a boat that may be a depiction of the Brendan Voyage

Explore more sites in Ireland’s Ancient East