Clonmacnoise Monastery

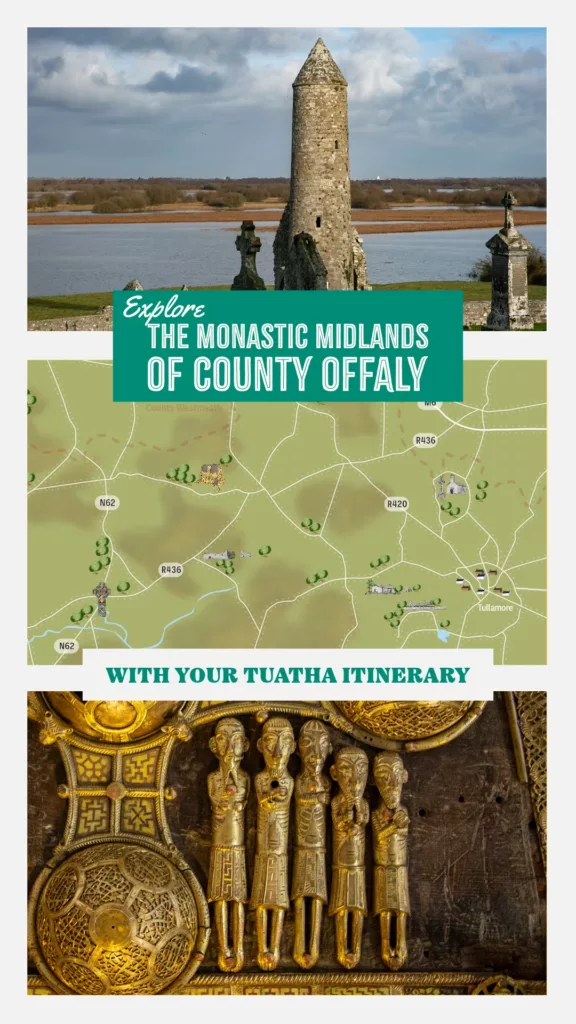

Clonmacnoise is undoubtedly one of Ireland’s most iconic historical sites. As an ancient monastery with high crosses, positioned alongside the stately Shannon, it features prominently in tourism advertising. But this is nothing new. Clonmacnoise has attracted visitors since it was first founded in the middle of the 6th century by St Ciarán.

Unlike many of the other early Irish saints who often came from privileged families, Ciarán was the son of a craftsman, but despite his relatively humble origins, soon gained a reputation for his intelligence and holiness. After completing his education, Ciarán became the founder of a small monastery on Hare Island in Lough Ree, before choosing the site of Clonmacnoise to establish another monastery.

This choice of location was incredibly shrewd. The name Clonmacnoise derives from the Irish Cluain Mhic Nóis, meaning ‘the Meadow of the Sons of Nós’, a probable reference to a pre-Christian dynasty who ruled these fertile plains alongside the Shannon. Though today it seems like a peaceful and somewhat isolated place, in the early medieval period Clonmacnoise was at the crossroads of the two major routeways of Ireland – the mighty River Shannon and the Slí Mór (meaning ‘The Great Way’), the roadway that traversed the country from east to west over glacial eskers, offering easy passage over the wetlands and bogs of the midlands. Clonmacnoise was also situated on the borders of two of the great kingdoms of early medieval Ireland – Connacht to the west, and Mide (Meath) to the east – and the site prospered from its close relations to both of the ruling dynasties.

For practical information about visiting this site Click Here

The Cross of the Scriptures and Cathedral • Clonmacnoise

The History of Clonmacnoise Monastery

Ciarán is believed to have died in the middle of the 6th century, not long after the foundation of Clonmacnoise. Different chronicles suggest dates between AD 543–549. But the monastery would become his great legacy, as it grew steadily in power and reputation. The famous Donegal saint, Colmcille (also known as Columba) is said to have visited Clonmacnoise towards the end of the 6th century during the abbacy of Alither, as recorded in Adomnán’s Life of Columba – a hagiographic account of Colmcille’s life and works, written around a hundred years after his death.

‘When they heard of his approach, all those that were in the fields near the monastery came from every side, and joined those that were within it, and with the utmost eagerness accompanying their abbot Ailither they passed the boundary-wall of the monastery, and with one accord went to meet Saint Columba, as if he had been an angel of the Lord.’

However, this welcome to Colmcille did not extend to his followers in subsequent centuries. The year AD 764 saw a bloody battle between the communities of Clonmacnoise and the nearby Columban monastery of Durrow, with over 200 men being lost. This was also echoed by writers such as Tírechán, who in around the year AD 700, complained that the community of Clonmacnoise forcibly held many churches that he claimed were founded by St Patrick. This was a symptom of the political power struggle of these great monastic sites. They were not always quiet, serene and holy places of contemplation. In Clonmacnoise’s case, it was surrounded by a large, thriving settlement. It was referred to at the time as Ciarán’s Shining City. These were Ireland’s first proto-towns, in the years before the Vikings arrived to establish true secular urban centres. This burgeoning lay community worked and farmed the large estates held by Clonmacnoise, there were masons, carpenters, metalworkers, and craftspeople of all kinds.

A fine medieval doorway into the Cathedral • Clonmacnoise

However the rigours of monastic life had to be upheld and ecclesiastic sites were strictly demarcated by enclosing walls known as vallum. Today we can see an enclosing wall and although this is probably post medieval, it follows the same layout as the earliest enclosing walls. However, because of Clonmacnoise’s importance in Ireland and the fact that elements of its layout follow biblical descriptions, Clonmacnoise had three enclosures. The first enclosure, which is the post medieval wall directly enclosing the site, was known as the Sanctissimus – this area was open to priests only; the second was Sanctior – this area was open to people who weren’t overly wicked; the last enclosure was Sanctus, an area open to all manner of sinners. All this division was derived from descriptions in the bible of settlements in the Holy Land and Jerusalem, and from its inception Clonmacnoise was seen to become Ireland’s equivalent to Jerusalem.

Until excavations were carried out in 1999, the position of the other two enclosures was unknown. However, excavation carried out to the south west of the old graveyard uncovered a wide and deep ditch and upon locating the second ditch, aerial photography and survey methods were employed to locate the third which was identified near the Nuns’ Church.

To date most of the evidence for settlement at the site is between the inner and middle enclosures (in the sanctior). It is also interesting to note that the nunnery (the Nuns’ Church and related buildings) is in a marginal position immediately outside the outer enclosure and half a kilometre from the Old Graveyard. Clonmacnoise was a large urban centre and it is noted in the annals that in 1179, 105 houses were burned there. At its height the monastery was surrounded by a large bustling settlement, with markets, craftsmen, labourers and farmworkers. It was surrounded by one of the largest early medieval populations outside of the Viking centres of Dublin, Waterford, Limerick and Cork. The positioning of the 3 concentric enclosures served to organise space within the site and allowed it to develop into a large nucleated settlement with a substantial lay population, while maintaining the integrity of its sacred core.

The monastery was connected to its broader hinterland and the wider world through the major routeways of the River Shannon and the Slí Mór. In the 1990s underwater archaeological excavations and survey was carried out by Prof. Aidan O’Sullivan, Niall Brady and Donal Boland on an early medieval wooden bridge crossing the River Shannon at Clonmacnoise. The remains of the bridge revealed sophisticated carpentry, and a timber was dated to AD 804.

The growing wealth and reputation of the monastery did not go unnoticed and Clonmacnoise was raided a number of times, mostly by warriors from rival Irish kingdoms, and in AD 842 and AD 845 by the Vikings. As the fortunes of the once mighty kingdoms of Meath and Connacht waned following the Norman invasions, Clonmacnoise’s wealth and status gradually declined over the centuries.

As the site is such a peaceful and tranquil place , it is difficult for us today to get a sense of what a vibrant and bustling city it would have been in its heyday. The roofless buildings that we see now are mere echoes of the ecclesiastical centre of the site, but the huge settlement all around this core is slowly becoming revealed through excavation and analysis of the historical sources. As more information comes to light the site grows in significance and grandeur. Founded by a saint, and the resting place for the kings, chiefs and warriors of Ireland, today Clonmacnoise peacefully slumbers alongside the mighty Shannon.

Today visitors can explore this incredible monastic complex and discover its story in the visitor centre. Clonmacnoise is also one of the highlights of our Dublin–Galway Road Trip Itinerary, available now for our members. You can also find a description of all the key features of the site below.

Annotated aerial image of Clonmacnoise showing key features • Offaly

The Cross of the Scriptures

A replica of the Cross of the Scriptures (tap image to see original) • Clonmacnoise

The Cross of the Scriptures is one of Ireland’s finest high crosses, and according to Professor Roger Stalley, it may have been created by the same master artist as Muiredach’s Cross at Monasterboice (you can hear a fascinating discussion in this episode of Amplify Archaeology Podcast). The cross was carved out of one solid block of sandstone. The depictions represents Christ’s crucifixion, death and rebirth. The large base, in the form of a pyramid, is thought to represent The Hill of Calvary or Golgotha where Christ was crucified, while the capstone represents the Holy Sepulchre – the tomb that Christ was held in after his death. The scenes which are carved out on the cross itself refer to the scriptures’ account of Christ’s death and rebirth.

The scenes on the west face of the cross are thought to represent guards at the tomb of Christ, the arrest of Christ and, in the centre, the crucifixion. On the other side of the cross scenes include the Last Judgement at the centre, and at the top of the cross, Christ with St. Peter. The bottom panel on the shaft of the cross is thought to represent St. Ciarán with Diarmuid, High King of Ireland, but it more likely depicts Abbot Colman with King Flann, placing the stake for a church in the ground. This is supported by an inscription on the cross, that states ‘A prayer for King Flann, son of Maelsechnaill, a prayer for the King of Ireland. A prayer for Colman who made this cross for King Flann’. It is known that Colman was the Abbot at Clonmacnoise from AD 904 to 926 indicating that the cross was possibly erected at the same time as the Cathedral in AD 909. On the base of the cross, hunting scenes can be seen which may allude to Kingship.

The real cross is in the Visitor Centre to protect it from weathering, while a convincing replica is out on site.

The Cross of the Scriptures (hover over to see original and replica) • Clonmacnoise

The South Cross

The South Cross (hover over to see original and replica) • Clonmacnoise

A replica of the South Cross (tap image to see original) • Clonmacnoise

The South Cross appears to be of an earlier date than the Cross of the Scriptures, with a mainly abstract design featured on it. There is only one figured scene which depicts the crucifixion of Christ. This cross, more than any of the other three, represents the transition from ornamental to scriptural carving. It also represents the transition from wood to stone, as it is believed that these crosses were initially displays in wood with attached metalwork panels. It bears a certain resemblance to other high crosses found in the Lingaun Valley of Tipperary and Kilkenny, like Ahenny and Killamery.

A very fragmentary inscription suggests that the South Cross may have been commissioned by the father of King Flann, Maelsechnaill Mac Maelruanaid, who was High King of Ireland from AD 846–862, and who also erected an inscribed cross at nearby Kinnitty, County Offaly. The crosshead and shaft are carved from one piece of sandstone, and slotted into the large base. The base is decorated with figures on horseback, along with more insular interlaced decoration. As with the Cross of the Scriptures, the original cross is located within the Visitor Centre and a replica is on site.

The North Cross

A replica of the North Cross (tap image to see original) • Clonmacnoise

The North Cross is believed to have been the earliest free standing high cross at Clonmacnoise. Today, all that remains is the shaft which is decorated on three sides and its base. Excavations carried out in 1990 determined that the cross was not in its original position. Nevertheless, the base which consisted of a large sandstone millstone indicates that it was always free-standing. Archaeologist Con Manning suggested that the re-used millstone base recalls Adomnán’s description of a similar monument at Iona in the 7th century. Although it was free-standing, only three sides of the shaft are decorated, and the east face remains uncarved. The repertoire of ornament includes interlaced human figures, animals and panels with interlacing designs, and Nancy Edwards has pointed to their close resemblance to manuscript decoration. Some of the designs are Irish in origin; others have similarities with stone monuments in Scotland. Like the other crosses, you will find the original in the Visitor Centre and a replica on site.

The fragments of two other high crosses are among the cross-slab collection in the cross-slab building at the site, and a further cross fragment is in the National Museum in Dublin.

The North Cross (hover over to see original and replica) • Clonmacnoise

Clonmacnoise Visitor Centre

The replica of a dairthech inside the Visitor Centre • Clonmacnoise

The purpose-built Visitor Centre was first opened in 1993 and it is run by the Office of Public Works. Inside you can book your place on a guided tour, or discover the exhibitions and audio-visual displays that tell the story of Clonmacnoise and early medieval Ireland. You can also find artefacts recovered during the excavations, and see the original high crosses that have been moved inside to protect from the effects of weathering. There is a reconstruction of a dairthech, a typical small oak church, such as the ones that may have stood here at Clonmacnoise prior to their reconstruction in stone.

The Clonmacnoise Cross Slabs

A selection of the cross slabs • Clonmacnoise

Along with the real high crosses, the remarkable collection of early Christian grave-slabs is the highlight of the Visitor Centre. There are over 700 examples of cross slabs known to have associations with Clonmacnoise, making it the largest assemblage known from either Ireland or Britain. The earliest slabs date to the 7th century and generally feature a simple cross design. As time progressed, their designs developed and became more elaborate. The slabs are all carved from sandstone, with the stone believed to have been quarried nearby. The volume of slabs and the quality of carving suggests that there was a specialist school of stoneworkers here at Clonmacnoise. The inscriptions of the crosses generally feature insular Irish script with the formula ORDOIT DO… (meaning A Prayer For…) and some include the words ‘poor’, ‘servant of’, ‘tonsured one’ or ‘most learned doctor’ which leads scholars to believe that the cross slabs generally mark the burial place of monks or other church figures. Other slabs feature the names of kings and we can deduce that the slabs were also used to mark those of rank and prestige within early medieval Irish society. The amount of high status burials here is also testament to how desirable and prestigious it was to be buried at Clonmacnoise.

A selection of the cross slabs • Clonmacnoise

Clonmacnoise Round Tower

The Round Tower • Clonmacnoise

One of two round towers at Clonmacnoise, it is situated on slightly higher ground in the north-west of the site. This round tower is one of the few examples that has its exact completion date noted in the annals. Chronicon Scotorum records that it was completed in 1124 by Ua Maoleoin, Abbot of Clonmacnoise, with help from Turlough O Conor, King of Connacht. Today the round tower is over 5.5m in diameter, and 19m tall. However, originally when it was built in 1124, the tower would have been much higher. Indeed, it is thought that over a third of the building collapsed in 1135 after a huge lightning storm. The tower was then modified and adapted to its current size and the eight openings at the present top of the tower were probably added around this time.

This round tower at Clonmacnoise would have had several uses when the site was a functioning monastic centre. It is now commonly believed that round towers would not have been a particularly effective defence against Vikings or other raiders, so the more common use for them would likely have been as a bell tower – in the Irish annals, round towers are generally referred to as cloigh teach or ‘bell house’. Another probable use for the round tower was as a marker in the landscape. The presence of a well situated and visible round tower may have acted as a sort of high status beacon to indicate to pilgrims in search of alms and a place of worship that a Christian site was within view.

Clonmacnoise Cathedral

Clonmacnoise Cathedral • Clonmacnoise

This building is the largest church in Clonmacnoise. According to the annals, this church was built in around AD 909 by Flann Sinna (also known as Flann mac Máel Sechnaill) – King of Mide from AD 877 and High King of Ireland between AD 879–916 – and Colmán, the abbot of Clonmacnoise at that time. The cathedral is the largest existing pre-Romanesque church in Ireland.

The church was originally a simple rectangular structure, but during the 12th century a new west door and east window were added and a sacristy was built to the south. Later, in the 13th century, the south wall was completely demolished and moved further north and, in the 15th century, an elaborate north doorway was added. This doorway features a finely vaulted masonry canopy with relief carvings of three saints: St. Dominic, St. Patrick and St. Francis. Although St. Francis’s head is missing, each saint is identified by an inscription. Another inscription in latin on the carving indicates that a dean named Odo commissioned the work. Odo, also known as Dean O’ Malone, died in 1461. The doorway is known as ‘the Whispering Arch’, if two people stand either side of the door and whisper into the grooves of the architrave, someone with their ear to the opposite side can hear them. The cathedral is the last resting place of Tairrdelbach Ua Conchobair, King of Connacht (buried in 1156), and his son, Ruaidrí Ua Conchobair, the last High King of Ireland, who died in 1198.

Clonmacnoise Cathedral • Clonmacnoise

Temple Dowling | Temple Hurpan

Exterior of Temple Dowling & Temple Hurpan • Clonmacnoise

This church is located to the south of the cathedral and the building includes part of a pre-Romanesque structure dating to the 10th century. This was extended in 1689 by Edmund Dowling of Clondalare. Prior to this renovation it was known as Temple Hurpan. A plaque recording this extension is located over the new doorway. Some of the remodelling includes non-functional antae which are projecting side walls, typical of the pre-Romanesque style in Ireland. This part of the church is now named after Edmund Dowling in recognition of his renovations and alterations. The church was later extended by the addition of a separate eastern chamber, probably largely used for burials and now named Mac Laffey’s Church. If you look closely at the interior of the north wall you might be able to spot an inscribed grave slab which was reused as building stone in the original church. Translated, the inscription reads: ‘a prayer for Dithraid’

.

Temple Melaghlin

Temple Melaghlin • Clonmacnoise

The building dates to the early 13th century and is Transitional – an Irish blend of Romanesque and Gothic – in style. During the late medieval period the church was altered and the doorway in the south wall was rebuilt. It has fine late 12th / early 13th century east windows. Another name for the church is Teampall na Rí, which means ‘the Church of the Kings’. Clonmacnoise became the main burial place of the Ua Máel Sechnaill Kings of Mide, the Ua Ruairc Kings of Breifne, the Kings of Uí Mháine, the Mac Cárthaigh Kings of Munster and the Ua Conchobair Kings of Connacht. This church is solely associated with the Máel Sechnaill Kings of Mide.

Temple Melaghlin • Clonmacnoise

Temple Ciarán

Temple Ciarán • Clonmacnoise

According to tradition this small church is the last resting place of the saint and founder of the monastery. It is thought that until the 17th century it also contained relics associated with the saint. This small and strangely shaped church is one of only six existing examples of the unique architectural type known as the early Irish shrine chapel. These were probably the earliest mortared stone structures in Ireland and Temple Ciarán is the only one of the six to have a true-arched doorway.

Radiocarbon dating which has been carried out on samples of mortar found between stones of the wall suggests it may date to the 8th or 9th century, making it among the very earliest mortared stone churches in Ireland. The soil within the chapel was in great demand for centuries as it was believed to have curative and other beneficial properties, it was particularly noted for protecting crops against disease.

Temple Kelly

Aerial view of the fragmentary remains of Temple Kelly • Clonmacnoise

Only fragments of this 12th century church remain, close to the north east corner of the cathedral. It is thought that the church was founded by Conor O’Kelly, King of Uí Mháine, in 1167 in place of an earlier dairtheach or oak church. Although the remains are fragmentary, the church is an important indication of building on the site in the 12th century. Like Temple Melaghlin and Temple Conor it is an important example of a royal mortuary chapel in this monastic centre.

Aerial view of the fragmentary remains of Temple Kelly • Clonmacnoise

Temple Conor

Temple Conor • Clonmacnoise

This church dates to the 12th century and as the name indicates this church was the final resting place of the O’Connors (Ua Conchobair), Kings of Connacht. All that remains today of the 12th century building are the west doorway which was built in the Transitional style, and the window at the east end of the north wall. Like Temple Melaghlin, it is a testament to the final period of royally commissioned worship towards the twilight of Clonmacnoise. It is a plain rectangular church which has been re-roofed and in use as a Church of Ireland place of worship since the mid-18th century. The church acts as a reminder that although Clonmancnoise today is mostly ruins and echoes of the past it continues to fulfil its purpose as a living place of worship.

Temple Finghín and Round Tower

Temple Finghín and Round Tower • Clonmacnoise

Temple Finghin stands at the extreme edge of the monastic site towards the river. The marshy and waterlogged nature of its immediate surroundings must have been similar in the early medieval period. The church itself is one of the two examples of the Hiberno-Romanesque style at Clonmacnoise and it is thought to date from around 1160–70. Another unusual feature is the south doorway. The integration of the tower, and the decision to build a doorway in the side rather than end wall, shows a deliberate reference to Cormac’s Chapel at the Rock of Cashel. The Romanesque chancel arch appears to have been damaged by fire and parts were reconstructed using limestone at a later date. The attached round tower is sometimes called the second round tower of Clonmacnoise and is about 16 metres high.

Temple Finghín and Round Tower • Clonmacnoise

The Pilgrim Path and Historic Graveyard

The stones mark the Pilgrim’s Path • Clonmacnoise

The monastic buildings are surrounded by a historic graveyard, and burials here go back all the way to the 7th century as people clamoured to be buried within the same soil as St. Ciarán to ensure resurrection into Heaven. In 1955 the core of the monastic enclosure, with the exception of Temple Conor, was transferred to the State by the Representative Body of the Church of Ireland. As the Old Burial Ground was more than full after 1200 years, Offaly County Council declared it to be closed and agreed to provide a new burial ground. The land adjacent to the Old Burial Ground was purchased and laid out as the New Graveyard. During grave digging in this area, the first ogham stone ever discovered in County Offaly was found, and led to a series of excavations by the late Heather King which revealed evidence for habitation and activity, as well as the great enclosures of the monastery. Today visitors can walk in the footsteps of the countless people who sought spiritual respite before them, following the Pilgrim’s Path for 400 metres or so to the Nuns’ Church.

The Nuns’ Church

The Nuns’ Church • Clonmacnoise

The Annals record that the Nuns’ Church was completed for Derbforgaill in AD 1167. She was the daughter of Murchad Máel Sechnaill, King of Mide, and of his wife Mor, daughter of Muirchertach Ua Briain. Derbforgaill is perhaps best remembered in history as a sort of Irish Helen of Troy. According to the more lurid accounts of the events that led to the Norman invasions of Ireland, it was Derbforgaill that was abducted from from her husband, the King of Breifne Tigernán Ua Ruairc, by Diarmait Mac Murchada, King of Leinster, in 1152. This led to such a deep enmity and spiral of revenge that some believe resulted in the Normans coming to Ireland at Diarmait’s request.

The Nuns’ Church is a beautiful legacy for this powerful medieval noblewoman. It is in a field to the east of the main monastic complex and is one of the finest examples of Hiberno-Romanesque architecture in Ireland. Serpents, plants and highly stylised animal heads are all represented, and if you have a keen eye, you might just spot a small romanesque sheela-na-gig type figure hidden in the decoration of the chancel arch.

The Nuns’ Church • Clonmacnoise

Clonmacnoise Castle

Clonmacnoise Castle • Offaly

The Normans left their mark on the site by constructing Clonmacnoise Castle to ensure they controlled the strategically important crossing point of the Shannon. The remains consist of a hall-keep within an enormous D-shaped earthwork enclosure. The castle was established in 1214, and it was under the control of Geoffrey de Marisco. It was on the front line from its foundation. The Annals of Loch Cé recorded an attack shortly after it was built in 1214: ‘Cormac son of Art, sent into Delbhna again, and his people carried off a prey of cows from the castle of Clonmacnoise, and defeated the Foreigners of the castle.’ There are no architectural features later than the 13th century in the fabric of the castle and it has been suggested that it may have been undermined and perhaps abandoned in the early 14th century, during the period of the Gaelic resurgence.

The Monastic Hinterland

Kilbegly Mill under excavation in 2006 • Roscommon

The remains of Clonmacnoise, as spectacular as they are, are just the very innermost core of the ancient monastery. It once had a wide hinterland surrounding it. This hinterland was well farmed by the lay community, providing the monastery with food, fuel and building materials. One of the most significant discoveries that shed light on this aspect of the monastery was Kilbegly Mill, a site I excavated in advance of construction of the M6 Motorway in 2006. Under a thin layer of peat in a hollow at the base of a field, we discovered a wooden mill, with its flume, millpond, undercroft, tailrace and more all perfectly preserved under the peat. We dated the site to between AD 650–850. This mill was built next to a small early church site, historically linked as a satellite site of Clonmacnoise. The mill was one of the finest examples of the era ever discovered in Europe. All the timbers have now been conserved and are in storage with the National Museum of Ireland.

Kilbegly Mill under excavation in 2006 • Roscommon

Upper left: Clonmacnoise seen from the banks of the Shannon • Lower left: Temple Conor and the second round tower of Clonmacnoise • Right: the Romanesque doorway of the Nuns’ Church

Top: Clonmacnoise seen from the banks of the Shannon • Middle: the Romanesque doorway of the Nuns’ Church • Bottom: Temple Conor and the second round tower of Clonmacnoise