Athlone Castle

Athlone Castle was built to defend a strategic crossing point of the River Shannon, forming a well-guarded gateway into Connacht. It is likely that the original Norman castle was constructed on the site of an earlier fortification established by the Ua Conchobair (O’Connor) kings of Connacht, as the Annals of the Four Masters record that a castle and bridge were built at Athlone by Toirrdelbach Ua Conchobair in 1129.

The present castle began to take its shape in 1210, when John de Grey was ordered by King John of England to build three castles in Connacht. However, just one year after it was constructed, the stone tower collapsed, killing nine men, including Richard de Tuite, the Lord Chief Justice of Ireland. The castle was quickly rebuilt, and historical records show significant sums were spent on its maintenance and upkeep throughout the late 13th and early 14th centuries.

During the chaos that engulfed Ireland in the wake of the Bruce invasion of 1315, the King of Connacht, Ruaidri na bhFeadh Ó Conchobair, seized the opportunity to attack the Anglo-Norman lands, and launched an assault on Athlone, burning the town and attacking the castle. The castle changed hands between the English and Irish many times during the 14th and 15th centuries, until it was finally recaptured by the English in 1537, as it is recorded in the Carew Manuscripts that the: ‘Castle of Athlone, standing upon a passage betwixt Connaught and these parts, is recovered, which has long been usurped by the Irish’.

The castle was repaired and became the residence of the Presidents of Connacht after 1569. However, the region was still not pacified.

Shortly afterwards, in 1573, an army of Scottish warriors, gunners and mercenary soldiers, led by the rebel James FitzMaurice FitzGerald, burned the town on the eastern bank of the Shannon. At the end of the 16th century, Athlone was threatened once again. This time by the forces of Hugh O’Neill during the bloody Nine Years’ War. O’Neill’s army burned and destroyed many farms throughout the region.

They approached Athlone with a strong force of 1,500 men. However, they found that the people of Athlone remained loyal to the English authorities, and so, without any support, the rebels withdrew. Despite the unsettled times, the early 17th century was a time of growth and development for Athlone, and an active merchant class thrived. The town became a borough corporation, that was entitled to return two representatives to the Irish parliament. Town-wall fortifications and gatehouses were built to protect the town, and those defences would soon be put to the test.

For practical information about visiting this site Click Here

Athlone Castle was built to defend a strategic crossing point of the River Shannon, forming a well-guarded gateway into Connacht. It is likely that the original Norman castle was constructed on the site of an earlier fortification established by the Ua Conchobair (O’Connor) kings of Connacht, as the Annals of the Four Masters record that a castle and bridge were built at Athlone by Toirrdelbach Ua Conchobair in 1129.

The present castle began to take its shape in 1210, when John de Grey was ordered by King John of England to build three castles in Connacht. However, just one year after it was constructed, the stone tower collapsed, killing nine men, including Richard de Tuite, the Lord Chief Justice of Ireland. The castle was quickly rebuilt, and historical records show significant sums were spent on its maintenance and upkeep throughout the late 13th and early 14th centuries.

During the chaos that engulfed Ireland in the wake of the Bruce invasion of 1315, the King of Connacht, Ruaidri na bhFeadh Ó Conchobair, seized the opportunity to attack the Anglo-Norman lands, and launched an assault on Athlone, burning the town and attacking the castle. The castle changed hands between the English and Irish many times during the 14th and 15th centuries, until it was finally recaptured by the English in 1537, as it is recorded in the Carew Manuscripts that the: ‘Castle of Athlone, standing upon a passage betwixt Connaught and these parts, is recovered, which has long been usurped by the Irish’.

The castle was repaired and became the residence of the Presidents of Connacht after 1569. However, the region was still not pacified.

Shortly afterwards, in 1573, an army of Scottish warriors, gunners and mercenary soldiers, led by the rebel James FitzMaurice FitzGerald, burned the town on the eastern bank of the Shannon. At the end of the 16th century, Athlone was threatened once again. This time by the forces of Hugh O’Neill during the bloody Nine Years’ War. O’Neill’s army burned and destroyed many farms throughout the region.

They approached Athlone with a strong force of 1,500 men. However, they found that the people of Athlone remained loyal to the English authorities, and so, without any support, the rebels withdrew. Despite the unsettled times, the early 17th century was a time of growth and development for Athlone, and an active merchant class thrived. The town became a borough corporation, that was entitled to return two representatives to the Irish parliament. Town-wall fortifications and gatehouses were built to protect the town, and those defences would soon be put to the test.

For practical information about visiting this site Click Here

Athlone Castle • Westmeath

Athlone in the turbulent mid-17th century

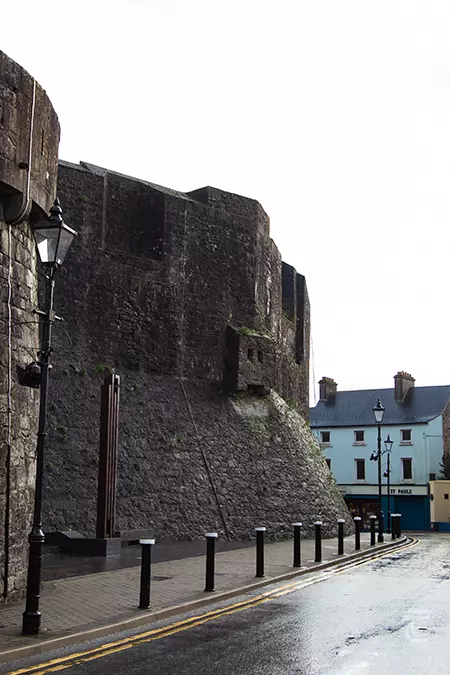

The central tower, or keep, of Athlone Castle • Westmeath

Athlone was embroiled in the dark days of the 1641 Confederacy Rebellion. The castle was held by a garrison who found itself surrounded and cut off by rebel forces, who were attempting to starve them into surrender. The soldiers and their families were saved by a temporary truce, which allowed a relief force to escort most of the garrison and Protestant inhabitants of Athlone back to the safety of Dublin. However, by a cunning ruse, the Irish Confederate forces gained control of Athlone Castle by exploiting the conflicting and confused loyalties of the remaining garrison.

The unrest in Ireland coincided with the English Civil War and the rise of Oliver Cromwell. After his victory in England, Cromwell brought the veteran troops of his New Model army to Ireland, where his short brutal campaign smashed resistance. Cromwell’s forces captured a succession of Irish towns, including Athlone. By 1653 all resistance had ended and Ireland was in Cromwell’s iron grip.

Those who had supported or enabled the Confederacy had their lands confiscated. Many Catholic landowners were moved across the Shannon to poorer and smaller estates in the west of Ireland, giving rise to the phrase ‘to Hell or to Connacht’. Athlone was the administrative centre for this enforced re-settlement of catholic landowners. By the 1670’s Athlone’s importance waned, following the abolition of the Connacht Presidency. The castle and much of the town was granted to the Earl of Ranelagh, a key financier of the flamboyant King Charles II who had been restored to his throne following the death of Cromwell.

The central tower, or keep, of Athlone Castle • Westmeath

The First Siege of Athlone Castle, 1690

The walls of Athlone Castle • Westmeath

Athlone Castle endured its greatest test at the end of the 17th century. Ireland had become a theatre of war for European and religious politics in the 1690s. The unpopular Catholic King of England, James II, was overthrown by a union of English Protestant parliamentarians. They invited his Dutch son-in-law, William of Orange to become King of England, Scotland and Ireland. William crossed to England in 1688, and he quickly gained large support across the land. James fled to France, where he was received into the court of King Louis XIV of France and who also supplied James with military and financial aid. The supporters of King James, known as Jacobites, raised a large army in Ireland. Irish Catholics flocked to the cause in the hope that a victory for James might reverse all the misfortunes of the Cromwellian Settlement. James set sail for Ireland with a well-supplied fleet, accompanied by experienced French officers to help him defeat the supporters of William, known as Williamites.

After their victory at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690, the Williamites effectively controlled the eastern half of Ireland. The River Shannon now became the key frontier, as the Jacobites held the vital strategic castles of Athlone and Limerick. In mid-July 1690, a 7,500 strong Williamite force, commanded by the Scottish General James Douglas, attacked Athlone.

Athlone Castle was defended by 2,000 men, led by the experienced veteran, Colonel Richard Grace. He ordered the abandonment of the eastern part of Athlone Town, and withdrew his forces over the Shannon, breaking down the bridge behind him. When he was summoned to parley terms for surrender, he defiantly fired his pistol in the air and declared that was the only negotiation he wanted. The Williamites lacked the necessary heavy siege artillery, and their field guns made little impression on the strong walls of the castle. Knowing that it would result in many casualties, General Douglas decided against trying to cross the river, and once he discovered that the defenders were to be reinforced, he lifted the siege and withdrew. The gallant defence of Athlone by Grace and his garrison, preserved the line and enabled the Jacobites to continue fighting the war for another year. For Athlone, the greatest test was yet to come.

The Great Siege of Athlone Castle, 1691

In the summer of 1691 the Williamites returned to Athlone to renew their attempt to capture the castle and forge a bridgehead across the Shannon that would allow them to enter Connacht. This time their army was over 20,000 strong, and it was accompanied by the largest artillery train yet seen in Ireland, with 32 heavy siege cannons and six mortars. The army was commanded by the experienced Dutch general, Godard van Reede van Ginkel.

At the outset, the Jacobite governor of Athlone was Colonel Nicholas FitzGerald, who had 1,500 men. In contrast to Grace’s defence the previous year, FitzGerald made an attempt to hold the East town against the Williamites. This was an attempt to delay the Williamites, to allow the new Jacobite army commander, the French Marquis de Saint-Ruhe, to muster his forces and advance from the west. Ginkel used his cannon to breach the eastern defences, forcing the defenders to fall back. As they crossed the river, they smashed down two of the arches of the bridge. Ginkel was now confronted by the wide river, a broken bridge and determined defenders on the opposite bank.

Saint-Ruhe took position on the western side of Athlone with the full Jacobite field army of 20,000 men. The troops were posted to garrison duty in relays. The garrison now faced the full weight of the Williamite artillery. For days, thousands of cannonballs, bombs and stones were blasted at the Jacobite defences in the west town. It was the heaviest bombardment in Irish history, prior to the 20th century. The riverside defence works were levelled and much of the east wall of the castle was beaten down. The town itself was reduced to rubble. The defenders were dangerously exposed. Stone debris and masonry, smashed into lethal fragments by cannon, flew through the air. One survivor described the scene ‘with the balls and bombs flying so thick, that spot was hell on earth’.

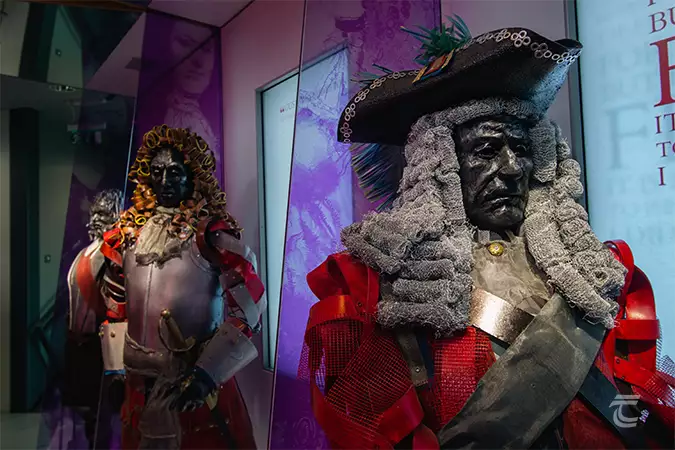

A depiction of Sergeant Custume • Athlone Castle

By the end of the seventh day, west Athlone was in ruins. Under cover of the bombardment a group of Williamite engineers began to lay planks across the broken arches of the bridge, to prepare for a frontal assault by Ginkel’s army.

An Irish sergeant of dragoons named Custume, and a band of ten volunteers, armed themselves with axes, picks and crowbars. They rushed from behind the remnants of the fortifications to smash down the nearly completed bridge. In response, the Williamite artillery once again roared across the bridge, accompanied by deadly volleys of musket fire. The incredibly brave volunteers managed to break away some of the timbers, but when the musket smoke cleared, all eleven men, including the valiant Sergeant Custume, lay dead. Inspired by their bravery, another band of volunteers rushed to break the bridge. Again they were met with a hail of musketry. Most of the party were casualties, but they managed to complete the destruction of the repair works, thwarting the Williamite assault plan.

Ever resourceful, Ginkel, explored the possibility of an assault across the old ford that had given Athlone its name. A band of grenadiers led by Colonel Gustavus Hamilton carried out a surprise attack. As they gained the opposite bank of the river they took the defenders unaware, hurling their grenades and charging into the breach. They moved so quickly that the shocked garrison retreated in the face of their speed and aggression. Immediately the victors manned the fortifications on the west side of the town to prevent the Jacobite army encamped outside from mounting a counter- attack. Meanwhile the Williamites repaired the bridge, allowing troops to advance across it to reinforce the grenadiers. When Saint-Ruhe saw the strength and deployment of the Williamite forces, he abandoned any attempt at a counter-attack. Despite the heroic defence of the town, after eleven hard days Athlone had fallen to Ginkel and the Williamites. Saint-Ruhe led the remains of the Jacobite forces further into Connacht, where they were heavily defeated at the bloody Battle of Aughrim just two weeks later.

The Later History of Athlone Castle

The siege left Athlone Castle in ruins. It was in a dilapidated condition until the end of the 18th century, when it was largely reconstructed to defend against the possibility of a French attack during the Napoleonic Wars. The castle was considerably rebuilt following a survey by Lt Colonel Tarrant in 1793 and further modifications took place during the 19th century. Today, Athlone Castle has a fine visitor centre which immerses you into the story of the siege. Don’t forget to also download your free audio guide before your trip!

Upper left: Athlone Castle • Lower left: the exhibition of the Second Siege of Athlone • Right: Entrance to Athlone Castle

Top: Athlone Castle • Middle: Entrance to Athlone Castle • Bottom: the exhibition of the Second Siege of Athlone